Some people build brands. Others build worlds. And every now and then, you meet someone who is quietly doing both, without rushing to explain herself.

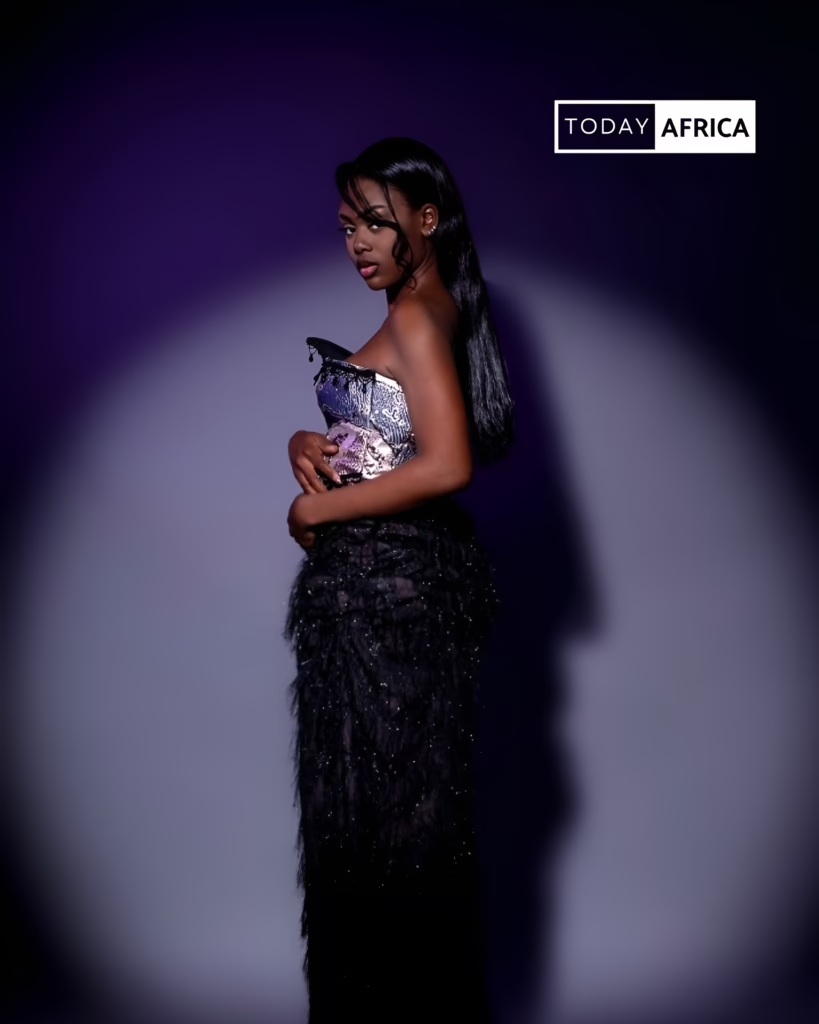

Adanna Ukabi is one of those people. Trained as an architect, deeply drawn to fashion, and founder of ADANNA, a made-to-order fashion brand focused on tailored fit and bold, artistic design.

She’s rooted in the responsibility of being a first daughter; she speaks about design the way some people speak about purpose. Slowly. Intentionally. Like it matters where the foundation sits, because everything else depends on it.

In this conversation with Today Africa, Adanna talked about why leaving architecture for fashion was never really a leap, how structure shows up in corsets, systems, and leadership, and why ADANNA is less about clothes and more about conversation.

Tell us more about yourself

Adanna Ukabi starts with where she stands in the family. A first daughter.

The kind of position that quietly shapes how you move through the world, how early you learn responsibility, how often you think in terms of “we” instead of “me.”

She says she cares a lot about community, about pushing narratives that benefit more than just herself. Purpose, to her, loses meaning if it is solitary.

She studied architecture at the University of Hartford in Connecticut, but even that feels like a technical detail layered on top of something older and more instinctive.

“Design has always been my love language,” she says, tracing it back to childhood. The pull was always about creation. The simple but demanding thrill of taking something from her mind and bringing it into physical existence.

That impulse, she explains, is who Adanna is.

What inspired you to leave architecture to build a brand in the fashion industry?

She laughs a little at how often she gets this question. From the outside, she understands why it looks like a harsh pivot. Architecture to fashion can feel like a leap across disciplines. But from the inside, she insists, it never felt dramatic.

Architecture and fashion, in her mind, speak the same language. They share principles. Scale is the obvious difference. Buildings are larger. Clothes are smaller.

But the questions are identical. “Can it stand? Does it serve its function?” She sees fashion as engineering with fabric, with math, with structure, especially when designing for the woman’s body.

She talks about Virgil Abloh, mentioning him almost gently. He studied civil engineering, not architecture, but his pivot made sense to her. Streetwear. Louis Vuitton. Creative direction that moved fluidly across disciplines. When you study engineering, she says, you start to see it everywhere. Fashion is not exempt.

Then there is her mother. Not a public figure, not loudly credited, but central. Her mother had already watched her pivot once, from biology into architecture. And when fashion entered the conversation, her response was simple and freeing.

Your talent is not good for only one thing. You can branch out. You have always been able to. Her mother had noticed her eye for aesthetics long before it became a business plan.

“She was really my push,” Adanna says. “She was the catalyst behind this whole movement.”

What architectural principle shows up most in your designs?

Structure. She returns to it again and again, almost like a mantra. Other principles appear, she admits, but structure dominates her thinking. It is why corsetry fascinates her. Without structure, she says, it simply cannot work.

She likes starting with the bare bones. What holds? What fails? How can the thing that makes something functional also become the design itself? In architecture, exposed structure can be beautiful.

In fashion, she treats it the same way. A jacket, a corset, a silhouette. The scale changes, but the logic does not.

Corsetry, especially, feels endless to her. It is flattering, versatile, can be obvious or hidden, and can sit quietly inside a garment or define it completely. She speaks about it with the excitement of someone still discovering its possibilities.

Structure, for her, is not limited to clothing. It shapes how she builds the brand itself. Coming from Nigeria, she speaks candidly about consistency and systems, about how rare and fragile they can be.

So she built internal systems deliberately, with the intention that the brand could run without her constant presence. One dashboard. Clear oversight. A foundation strong enough to hold everything else.

“If your foundation has cracks in it,” she says, “everything else really doesn’t matter.” Buildings, businesses, garments. The rule applies across the board.

Read Also: The Research Disaster that Pushed Kamil-Bello Furqan to Build Tweakrr

ADANNA feels like a virtual language, so what story does your brand tell in its own words?

“ADANNA isn’t just a fashion brand,” she says, and she means it literally. She calls it a conversation. Clothing is only one element. The product is fluid. The world around it matters just as much.

She quotes Virgil Abloh again, about a candle in a garage versus a candle in an art gallery. Context transforms meaning. So ADANNA is about building a world. How you approach people. What you say. What you offer beyond the transaction.

If all she does is put out clothes, she says plainly, she has failed as a creative director. The clothes must speak, yes. But the artistic direction goes further. ADANNA tells the story of a woman. Specifically, the first daughter.

In Igbo culture, Adanna is the name given to the first daughter. But she is quick to say she is not the only one. Every culture knows this role, even if it calls it something else.

The weight, the expectations, and the daily negotiations. What first daughters think about. What they talk about. How they show up.

That is the woman she designs for. That is the conversation she wants the brand to hold. ADANNA, to her, should feel alive. Responsive.

A vessel that can engage with social topics, with moments, with shifting realities. That is why she designed the studio the way she did, with a photography space ready to create whenever a story needs to be told.

“It’s not just a fashion brand,” she repeats. “It’s a conversation.”

What emotion do you hope someone feels the moment they put on ADANNA?

Courage comes first. Then self assurance. Purpose. She is clear about that. Intentionality matters to her.

She talks about the well known but still powerful truth. When you look good, you feel good. You walk into rooms differently. You close deals faster. There is data to support it, but she doesn’t need the studies.

She wants ADANNA women to feel like the boss of their own lives.

The made to order model reinforces that feeling. A piece tailored to you. A one of one. Something designed with your body in mind. She smiles at the idea of a woman explaining that her garment was made specifically for her.

There is bravado in that. A straightened back. A quiet confidence.

She does not want ADANNA to be the equivalent of a t shirt and leggings. She wants it to be the outfit you reach for when the day feels heavy and you still need to conquer it.

“Today was tough,” she says, “but I’m tougher.”

Why choose the Made-to-Order model when fast fashion is easier and cheaper?

She does not romanticize it. Made to order is slow. Intimate. Demanding. In a microwave society, she knows it can look like a disadvantage. That is precisely why she chose it.

She cares deeply about what leaves the brand. Every piece. Every order. She wants customers to know that their garment was considered. Looked at. Thought through. That level of care, she believes, creates security, especially for women.

Practically, it makes sense too. Fewer inventory issues. Less waste. Production that responds to demand instead of guessing at it. Sustainability, for her, is not a buzzword. It is a natural outcome of being intentional.

“I hate being wasteful,” she says. Fast fashion may be cheaper, but she is blunt about it.

“I don’t do cheap. I don’t live my life cheaply.” The standard you move at shows. She wants ADANNA women to be invited into that standard with her.

Read Also: “Nobody Deserves Hunger.” The Purpose Driving Victoria Olabode and Her Business

What’s one thing the world misunderstands about African luxury?

She almost pauses here, because to her the misunderstanding feels obvious and strange at the same time. African luxury, she says, is rich. Deeply rich. If anything, Africans do luxury best.

She talks about bravado. About how Africans carry themselves. The colors. The versatility. The lives lived loudly and fully. Luxury, to her, thrives on interesting people, and she sees Africans as endlessly interesting.

She acknowledges her bias, but she owns it. She is an African woman. And she feels African luxury has been undermined, owed a different kind of recognition.

Richness, she says, is in the DNA, in our food, in our language, and in our women.

Her work may not follow traditional markers of African luxury, but she insists the culture still shows.

Flamboyance finds its way in, whether intentional or not. It always does.

How do you scale a Made-to-Order brand without losing the soul that makes it special?

This is not a question she answers once and moves on from. It is one she asks herself repeatedly. Soul, to her, is not static. It evolves. But it must be protected.

Scaling without losing it starts with leadership. With intention. With integrity. As soon as those shift, she says, the soul follows. Numbers cannot come first. Purpose has to lead, even when it feels backward.

She talks about checking in with yourself. About burnout, pace, and about knowing when to slow down. External validation, she warns, can be dangerous. Not every opportunity is an opportunity. Some are distractions.

Longevity, in her view, always beats speed. And preserving the soul of the brand is a daily responsibility, not a one time decision.

You are building a sustainable production system in Nigeria, what challenges you to innovate daily?

She is realistic about where she is building. Inconsistencies exist. Limitations too. But she believes lack can sharpen ingenuity.

Understanding her team’s reality matters to her. Their lives outside the studio. The struggles they carry in with them. Innovation, for her, often looks like asking how to fill gaps with what is available. How to get resourceful. How to get crafty.

“If there’s a will, there’s a way,” she says, and she means it practically. Wi Fi issues. Water. Tech failures. They are problems to work around, not excuses to stop. She feels a responsibility to build something stable enough for her team to thrive.

It is tough, she admits. But it is also a privilege. Being forced to think. To refine. To improve. Trouble reveals weak spots, and weak spots can be strengthened.

Read Also: Meet Richard Afolabi, the Founder Using Tech to Preserve African History

You are building a community around your brand, who’s the ADANNA woman?

She describes her without hesitation. Decisive. Tenacious. Audacious. A woman with authority. Someone who goes after things others might call crazy.

She is many things at once. Mother. Sister. Friend. Daughter. A catalyst. A leader. A conversation starter. Unforgettable, whether loved or questioned.

ADANNA, she explains, is not meant to create this woman. It amplifies who she already is. When the clothes come off, the woman remains. That matters deeply to her.

She designs for women with strong character and a strong sense of self. Women who know what they want. Women who are picky because discernment comes with clarity.

She knows her audience. And she is comfortable with not being for everyone.

What have your U.S/U.K customers taught you about the global appetite for African luxury?

They have confirmed what she already suspected. People are craving African luxury. Especially in the diaspora. There is a desire to see familiar cultural energy represented on a global stage.

She heard these conversations while living in New York and continues to hear them online. The appetite is there. The moment feels right.

She names other African brands and designers she admires, women who are already contributing to this global conversation. Her goal is not to replicate them, but to join the dialogue in her own way.

To push toward becoming a global luxury fashion house as an African woman.

What role does storytelling play in convincing the world that Africa is not emerging, it’s leading?

Storytelling, she says, is something Africans mastered long ago. She calls it their lane. Their strength. Their inheritance.

Africans speak poetically, she explains. Wisdom is layered into language. Stories carry depth, humor, history. Many of those stories were forgotten or ignored, but they never disappeared.

She wants ADANNA to use storytelling to connect the dots. To make it undeniable that Africans are not catching up. They have been leading quietly. Through visuals, colour, and music. Afrobeats. Fashion. Art.

She compares it to diamonds in the rough. Valuable long before they are discovered. Africans have been doing their own thing. Minding their business. The world, she believes, will catch up eventually.

Read Also: Niza Aritha Zulu: From Student Idea to Patent-holding Agritech Innovator

What’s the boldest risk you have taken creatively and how did you change your brand?

From the beginning, she refused to follow expectations placed on her as a Nigerian woman. Unconventional is how she describes herself. Rules, stigmas, status quo. None of them feel binding.

Her first release set the tone. Two outfits. Multiple pieces. Entirely crochet. Labor intensive. Not scalable. But intentional. She wanted to experiment. To test. And to signal clearly that expectations would not be met in predictable ways.

Later came “Too Hot to Handle.” Ruffles. Beading. Crochet. Draped beads. Familiar techniques used differently. Always searching for shock factor. For memorability.

That approach locked in her design principle. Boldness. Polarity. Identity. She believes a fashion designer needs an identity strong enough to stand on, flexible enough to evolve, but grounded in clear principles. Boldness, for her, stabilizes both her vision and the brand.

Where do you see ADANNA in the next five years?

She sees community first. A strong base in Lagos. Reconnection with New York. Expansion in the UK. But more than geography, she sees women united across locations in one conversation.

Pop ups. Trunk shows. Travel. Meeting women face to face. She finds women deeply inspiring and sees them as the driving force behind expansion.

She imagines ADANNA as a broader conversation. More transparency. More access to process. Events with meaning. Conversations beyond fashion. She speaks openly about having sickle cell anemia and wanting to support causes that help women and people more broadly.

ADANNA, in her vision, stands for something. Wearing it means aligning with that purpose. There will be more collections, runway shows, collaborations, and new faces. But at the core, she wants people to associate the name ADANNA with intention.

Not linear. Not scattered. Balanced. Purposeful. A brand that speaks before it sells.

Contact or follow Adanna Ukabi:

Leave a comment and follow us on social media for more tips:

- Facebook: Today Africa

- Instagram: Today Africa

- Twitter: Today Africa

- LinkedIn: Today Africa

- YouTube: Today Africa Studio