John Nyongesa, the founder of Safiri Salama, lost his father in 2003. More than a decade later, his son who was four years old at the time of his grandfather’s demise asked him a few questions that led him to create a memorial website for his father.

“The inspiration came accidentally. My son, Jason who turned 18 in 2018 provided it. The loss of an uncle with whom he shared a clan name, inspired questions about our family, our clan and specifically, his grandfather (my father). He could not remember much of him, and his curiosity generated question after question. The most pointed out was; “Why isn’t granddad online?”,” Nyongesa told Today Africa.

“I fumbled to answer that. If it wasn’t online, it did not exist. It was clear. My father was forgotten because, beyond a few pictures, he couldn’t be found. I felt guilty.”

At the time, Nyongesa said he did not find a Kenyan or African-focused memorial website that he could use for his dad. Within three months, he created a memorial website for his dad. “During the process [of creating the website], dozens of my friends expressed the same desire: to preserve their memories of lost loved ones for future generations. So I expanded my personal website into a public memorial website,” he added.

Nyongesa started the development of SafiriSalama.com in 2018 as a public memorial website taking its name from the Swahili words “Safiri Salama,” which translates to “Travel Safe ”. This website has now evolved into a funeraltech startup, the beta version was rolled out in November 2022. A year before the rollout, he was joined by Steve Lelei, an actuarial scientist and Edith Orwako, a Project Manager, as co-founders.

Tell Me More About John Nyongesa of Safiri Salama

My name is John. I’m the founder of Safiri Salama, basically co-founder. There are two other co-founders. My background is in communications. I’ve been a journalist, a producer, a marketer, TV anchor, sports commentator, then went into communication strategy.

And I spent quite a bit doing that. And then at the ripe age of 48, decided to pivot into tech. So I will say almost over 28 years of experience in different aspects of the communication industry. So at 52, I’m an embodiment that tech is not for the young only. What I feel is that what I’m doing now is a collection, is a sum of collective experiences that I’ve encountered in my journey as a journalist, as an advertiser, as a broadcaster, as a communication strategist.

What Inspired You to Start the Safiri Salama and How Did You Identify the Need of Innovation in the African Traditional Death Care Industry?

Actually, it was an accidental discovery. The only thing that goes for it is that I’ve never been exactly traditional in my outlook. Even when I was in communication, when we ran our agency, we used to call it a gorilla agency.

Basically, we operated so much outside the mainstream. And even as a journalist, I was never fully hired when I did the Kenya Broadcasting Corporation, when I did write as I was always a freelancer. Because I preferred actually trying to see things a different way.

Personally, I have a twenty four year old son, who is turning 24 this year. And when he was 18, one of the things that we were discussing. Because we consider 18 to be the right passage year, it was that he couldn’t, as he tried to find out who he was, his tribe, his ethnicity, his identity, and the issue of his grandfather came up.

MY father, his grandfather, died when he was four years old. So he could hardly remember who he was. And the fact that he had also lived outside the country, he went to school in a neighboring country, he could hardly speak vernacular. And so his quest for identity was very important for him. In the process, he asked some very piercing questions, who we are, what we are like, what makes him different.

And the other question that came up was, what can I tell him about his grandfather, his community? One thing that came across was that there was very little that was taught to help him. And one of the big questions he asked is, why isn’t Granddad online?

Because I gave the lame excuse of, well, you know, in 2003 when he passed on, the internet was not such a big thing. He was like… but history is online. The rest of history is online. And so my father was a historian. That by itself was an indictment of me having let his memory slide.

So I actually looked for a couple of things I could do, like build a private website, because I’d worked as an advertising agent, so I knew all about design and stuff. However, immediately I tried to check whether there were good existing websites that would accommodate his memorial. I realized most of them were actually based so much on a Western orientation of it.

I just put together a small website template, a WordPress template for him as a memorial website. In the process, actually, I managed to get something that would put together his history because he had aged for a long time, before he died. And he took time to actually pen down his autobiography in an exercise book.

So that was a good time for that. It was everything, including how many cows he had paid for dowry for my mother, and those kinds of stuff. It meant for very interesting reading because he had left this book with us as a family. But once somebody’s buried, we had to go back there to actually dig in. But after putting this together, and that included now ferreting around to find these pictures, which were in all sorts of storage modes.

I talked to a couple of friends about this and they suggested, you know what, John, maybe this is a service that other people could use. Because actually we all cannot, we don’t store the history of our fathers and grandfathers. We normally put them in something called the funeral booklet or the memorial booklet. But after the funeral, nobody knows where it goes. And where did all those pictures go?

So in asking around, people are like, why don’t you actually turn this into a service that people can use? And so I reached out to different people, including a bereaved family on, would you use this? Because all it had was a memorial where you could have pictures and notifications for when the memorial and birthday is up and a place where to put tributes and a place where to put pictures.

But the first reaction I got when I dealt with the family was, it’s important, but it’s not the most important thing today. Because they were freshly bereaved. And they were like, I don’t think for us, storing memories will be the biggest thing we want to do now. What we are trying to do is to raise money to bury a person, coordinate people, and make funeral arrangements.

Basically, they were more immediate about what they needed. And my thinking was that was the first reality check of whatever idea I had. I found that very entertaining because that is a market check. And so what they were saying, we are used to death notices and we’re used to funeral announcements. Is this a funeral announcement? And so went back into, memorials look like a good idea, but they were suggesting we needed to announce a death.

And the announcements that were existing in the market were very expensive. So it led me into another phase of what actually were the issues around the market. You realize obituaries are so expensive, less than 10% of people were using them in newspapers and on radio. Yet one of the most important aspects of any culture in Africa is announced, the first step is to announce a death.

So we said, actually do it. But the other thing you realize is why obituary is more expensive. Newspapers had shrunk in readership. Radio stations were much more fragmented. It made it much more expensive. So people were resorting to either putting death announcements on Facebook, which were not suited for it, or putting it on WhatsApp, creating WhatsApp groups. Then something else came up. People are complaining about not just the cost, but the ownership of the death notice.

Most newspapers own the notice. You pay them. They float the notice for you, you want to amend it, you pay again, and so you actually don’t control it. Then something else that comes up is that death notices in the newspapers and on radio are not stored in a retrievable manner.

Basically, you’ll find lots of radio stations read out the funeral announcements live. And most newspapers actually float it for the day and don’t put an online version of it. So if you wanted to retrieve it, you actually can’t.

So an issue came up, especially when you understood that death notices were not just about announcing a death, they were the history of a person. It detailed family members, who the person was. And so we said, why don’t we create a modern version of a death notice that is digital. That’s online, that is shareable, that is cheaper, and which can be owned by the family, and it’s a one-off event.

So that we are into doing that and later on we’ve improved it. We said, normally Africans don’t really bury within cities that much in cemeteries, they bury in up countries. So why don’t you actually provide maps for burying, for directing people who are coming for the funeral? When COVID came, it introduced the aspect of live streaming. So why don’t you have your live streaming links there as well? So a couple of modifications we did actually improve what a death notice can

Then another issue came up when we figured it out, when we talked to families and they were like, do you know what hurts us the most? It’s the cost. The cost of finding suppliers. It’s the time. It’s terrible because we don’t actually treat the funeral industry as a formal industry. And that means it’s very fragmented. There are all sorts of suppliers in small outfits in all sorts of different places and they have all sorts of services which you may need, but which are not actually classified as funeral services.

I’ll give you an example. The lawyer who writes a will is not actually seen as a member of the funeral industry. The person who actually does catering, the person who actually does event organization in Africa is not seen as part of the funeral industry. What are seen as part of the funeral industry are the people who provide the house, flowers and funeral homes.

So we thought, and then one of the things that happened with this fragmentation, not serious marketing around it, a culture of silence in which you cannot advertise a funeral service or a product. I mean, go through mainstream media. You will never see advertisements about a funeral service.

Death is Seen as a No-go Area in Africa. Everybody’s Kind of Scared of Dying

Yet it is the one thing that we all confront. And it’s even worse than that, that when a death happens in the West, you have a funeral home to go to and a funeral director to help you plan. More like, you know the way you do wedding planning.

In Africa, it is friends and family planning without any prior experience around it. What that exposes them to, there’s a lot of time wasted because they have to physically go to see the supplies and the products like coffins and caskets are made on this street. You have to physically go there. And that gave us the idea about how about, beyond creating this funeral platform where you can advertise, where you can have death notices, have memorials.

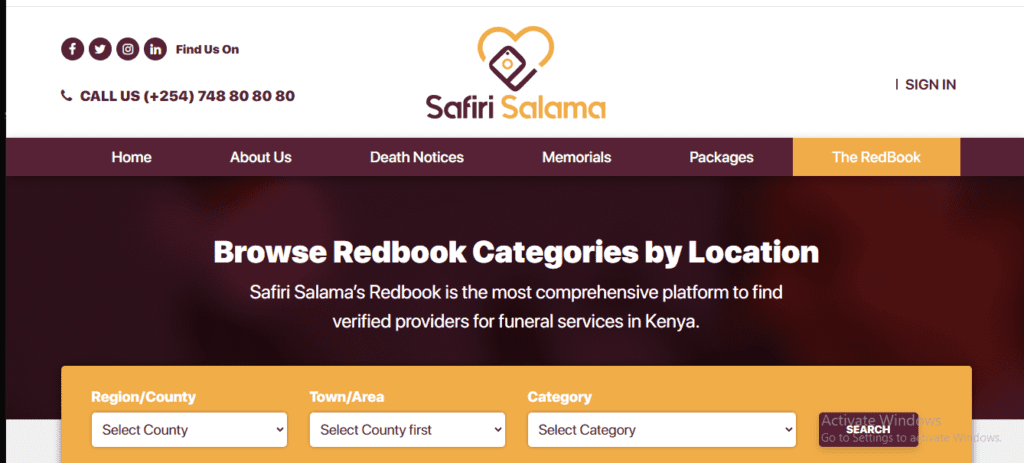

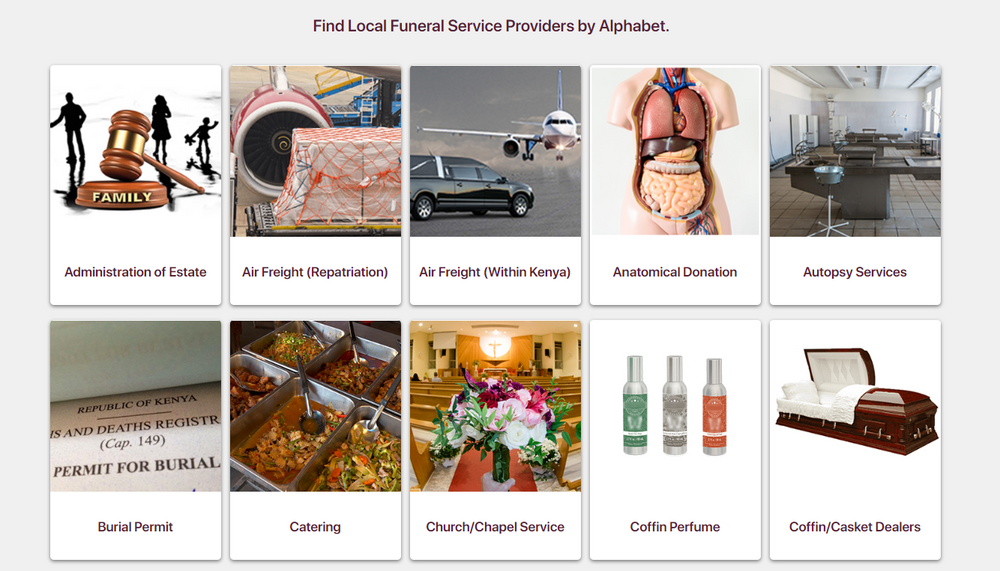

Why can’t you also have a directory of funeral service providers? We call it the Red Book. So we ended up creating three products – Death Notices, Memorials, and what we are calling the Red Book.

Basically, the yellow pages of the death industry, but then very extensive because it includes lawyers, people who work directly in the industry, event organizers, or we even found people who make funeral outfits, mobile toilets, people who stream, directors, counseling, I mean, grief counseling is part of that. So we thought, why don’t we just have this one stop place where people can go. Because, while Africa is first adopting technology and is helping us how we buy, how we shop, how we find items. The death industry is untouched by technology. And as such, it makes organizing a funeral a traumatic experience.

One you don’t have the experience, two you don’t have the time because barriers have to happen within a specific period and COVID brought this home. And within that period, you’ve got to make very many decisions without any guide or help. So that’s what actually created Safiri Salama for us.

Safiri Salama basically in Swahili means, go well or travel well. It’s a common phrase used during funerals.

How Did You Meet Your Co-founders and What Convinced You that They are the Right Partners to Work with You?

I’ve always been in the media industry and the media business. And that’s why I told you, I think what I’m doing now is a culmination. Because having worked as a freelance journalist, having worked in the newsroom, having worked in production, having created and headed an advertising agency. One of the things you learn is that the people you partner with are like a marriage.

And I have always tended to fall back on people I have worked with before and worked on different kinds of assignments so that you understand their temperament, their view of building stuff, their sense of adventure. For me, two years after I started building the prototype, I actually went back to one person who was the head of management, who was an administration head at my advertising agency, the one that I ran, Public Consulting Practice Group and she’s called Edith.

Worked with Edith since she left college in 2007, 2008, when I was doing programming at a broadcast station. She came in as an intern, she worked on one of my programs and she was pretty outstanding. And we offered her a job when she was done with college. And so we have a partnership that has run over 17 years in different aspects. She’s traveled outside the country going to do her double master’s degree. But she came back home and I was like, let’s complete what we started.

Then while I was working with different clients, I ended up also engaging an actuarial scientist who would actually work with a lot of clients with regard to predicting sales, working the numbers, crunching the numbers. He’s Steve. And I reached out to Steve and I said, look, I’m trying something here that’s really unique. I will need to have a very good perspective of it. I will need to have a very good outlook of the numbers because if we are going to do a tech business that’s dealing with this, we need to have the right information.

And so that’s how both Steve and Edith came on board as co-founders of Safiri Salama. So basically between us, we shared over 17 years of knowing each other, which made it a bit easier.

When it Comes to Funerals, the Cultural Sensitivity Surrounding it is Quite High. So How Do You Approach Building Trust with Customers and Communities Over There in Kenya?

That’s actually the key question to understanding what we are calling a death tech. Many people say we are Africa’s first death tech. I was discussing this with an anchor friend of mine because we want to do a radio campaign later on in the year. And the first thing he said, you’re not going to use such words on my show. I use words like farewell. I have a morning show about death.

However, I think the first thing that you learn from having worked in the advertising industry and the communication industry, the first thing you learn is tone. The other thing you learn is about understanding an audience. Nobody may want to talk about death upfront, but many people may want to talk about memorializing people they love. If the language is love, it’s different. It’s easy to talk about love. It’s easy to talk about respect and honoring those who went before us.

We normally have that in conversation. And that’s exactly what the entire funeral right is. It’s a right of passage. The other thing that we did was to actually adopt policies on our platform that borrowed from our experience in communication. And one of it was the look and feel. If you look at the website, Safiri Salama, the colors, the shade, the tone is not exactly what you’d find on a memorial website.

It is basically warm, unless when you, unlike when you look at most newspapers and when you look at pictures on the obituaries, the people really look dead. I mean, no disrespect, but we would like to celebrate people. And so we allowed people to actually upload pictures, profile pictures on the death notices they create. And if they are on the memorial, people create what look like albums. So basically it is a much lighter version of looking. It’s like you’re looking at your Facebook page. So we adopted a design style that was warm.

Then the other thing we did was we gave it a name. Safiri Salama is a common phrase in Swahili, which people actually use when bidding farewell to a loved one. Safiri Salama means go safely, travel to the next world safely. So it’s a phrase that people know. And the other thing we did, was using our communication background to turn the products that you’re offering the public, the services into products.

They’re not tangible products, but we turn them into products in the sense of our Safiri Salama death notices even have a look and feel to them, a logo like a product. Memorials have their own logo as a product. Instead of calling this the Yellow Pages of Death, our directory, we basically called it the Red Book and created a site that was so warm and told a lot of the funeral service providers, we’re offering you some because they didn’t even know how to advertise their products.

Most of them will send you pictures of coffins via WhatsApp. We are like, no, no, no, no. However, if we create a mini website for you inside our website, so that when I come, I can go and look at these coffins. But when you click inside, you’ll find companies. When you click some more, you’ll find a company’s profile, their working hours, a map leading to where they are, their unique selling points, and now even a catalog of the coffees they offer.

And at the beginning, it was very important, we told them the quality of the pictures we’ll accept have to be of a certain standard, like the way Amazon will do it. And they’ll be like, no, I just take some fun pictures and send them, say, no, those are not going on our website. So we even get to hire a cameraman to go and take pictures of their products so that we put them on our website so that they are warm and not dark gray, and stuff like that.

But more importantly, well, it will be our attitude. The people we hired, we emphasize on emotional intelligence. We had to evaluate who we hired because you’re working and you’re meeting families at their worst time possible when they have lost someone. And you must have a level of emotional intelligence that works with this. The other thing was then partnerships. Where to resort to partnerships? Because in Africa, funerals are about communities. And so it’s about tribes and clans. And one of the things you realize, it doesn’t matter whether you are in your 90s, whatever you were, even a gangster, you’ll be buried by a priest or an imam.

So partnerships with religious organizations became part of what we’re doing. Then one of the other things was also partnerships with funeral homes. And now we are looking at cultural organizations to partner. And the biggest thing we are talking about, this is not just about selling death care services. This is about storing memories of ourselves. So I guess the approach does matter in how you’re communicating this very sensitive subject.

Click to read part two and part three of this interview.