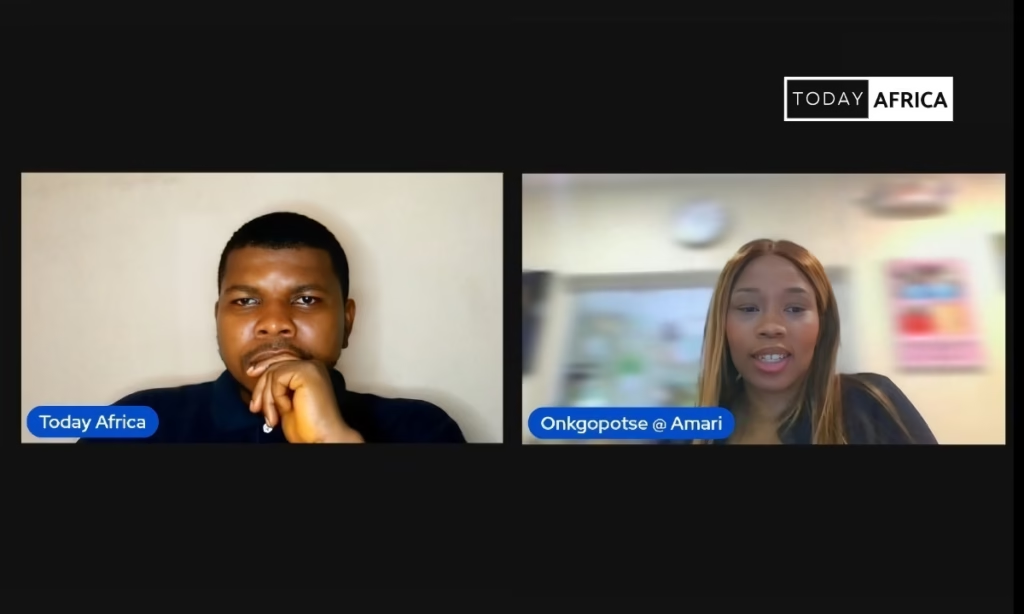

Onkgopotse Khumalo is a South African entrepreneur and the founder of Amari Health (formerly The Pocket Couch), a health tech startup that aims to democratize access to mental healthcare.

Her early professional journey saw her navigating financial services in the investment and portfolio management space, later transitioning to a management consultant role at McKinsey and Company.

She then ventured into entrepreneurship after identifying that what she had initially thought was a problem unique to her own circumstance, was in fact more widespread across the globe.

It was her personal journey trying to find avenues to better their mental wellbeing, that catapulted her journey into entrepreneurship, ultimately founding the startup with which she has a strong personal nexus.

Onkgopotse Khumalo shared with Today Africa about her entrepreneurial journey.

Tell us more about yourself

My name is Onkgopotse Khumalo, I’m an entrepreneur and a mother, first and foremost. I am based out of Johannesburg, South Africa and I come from a family of five. So I have two other siblings and all of us were born and raised in Johannesburg, South Africa.

I studied at the University of Cape Town, completely unrelated to what I ended up building. But I studied finance and I then navigated a career in the portfolio management and asset management space and then management consulting.

I worked a little bit in freelance consulting as well as SME development until I ultimately navigated into entrepreneurship. I come from a family of scientists. So my mother is a doctor and my dad is an engineer. So our upbringing was very rooted in academic excellence and pursuing excellence.

That was kind of the major part of the household. It was like a meritocracy. You’re either doing well or you’re not getting what you want. And so those are kind of the principles we were raised by.

I was fortunate enough to be raised in an environment where my father is a professional working in the engineering space and my mother has always been an entrepreneur. So I had both lenses of what it would look like if I were to pursue either route. So they live in very different worlds.

And so that I noticed very early on. My mom is a visionary and she has a lot of grand ideas and she’s very innovative and almost abstract in the way she thinks about the world, which has served her well.

Because she has done an incredible job in building her own business alongside myself and my sister. But my father is an engineer and he’s worked in corporates and as a civil servant as well and very structured person oriented.

So it’s very interesting to grow up in an environment where you get to see the best of both worlds. As a child, sure, it was a long time ago but I would say I was very curious from a very early stage around, I had a lot of empathy.

And I think that comes from a couple of things. So I grew up with a brother who, coincidentally, yesterday was Autistic World Autistic Autism Awareness Day. So I grew up in a household with a brother who is on the spectrum.

And I think that really helped shape my view of the world around how to think, support and adapt to better support people who think differently. How to really lean into being patient with people, how to really understand the why behind what people are doing.

And over time, it really grew into this, I would say, deep curiosity around human behavior. Unbeknownst to me, I hadn’t really thought about building in mental health or anything of the sort.

I had a lot of subconscious experiences that affected my subconscious that in hindsight, I now realize, okay, this picture was forming from early on. And so I think that the family environment really began to shape a lot of what we’re seeing now in terms of what we’re building with Amari, which I’m passionate about.

Yeah, and I think my personality, I’m very personable, I would say, quite sociable. I would say I’m a bit of an introvert. I was called an ambivert. So I can dovetail between both extremes of the spectrum, depending on what the situation demands of me.

I love understanding the why behind people’s what. And obviously very passionate about mental health for various reasons, a large part of which has to do with my personal experiences and observing and being affected by the experiences of others around me and so far as mental health is concerned.

What inspired you into starting your business in the mental health space?

It’s a very good question and I get asked a lot. I think outside of the personal experiences subconsciously as I was growing up that was shaping me. What really solidified the transition was my personal experience with mental health challenges.

So I was working in a very high pressure, fast-paced environment and in the professional services space and not getting much sleep. It was kind of a whirlwind at that stage and ultimately I struggled with severe burnout and was forced to take a break.

Oftentimes we will say, you nurture your body and allow yourself to take breaks because your body will force you to do it eventually. And at that time it will be at the most inconvenient time.

So I struggled with burnout and anxiety in that space which was so debilitating that I had to be admitted and had to be in an environment where I was forced to really confront this issue of race and mental health.

And in that space, I was lucky enough to have a psychologist and have access to a psychiatrist and medical care and a supportive enough ecosystem.

But what I really struggled with in that process was, one, finding a language to articulate in the professional environment what I was struggling with because I didn’t feel like there was psychological safe spaces in the work environment for me to do that.

Two, I struggled with finding the right support at the time I felt I really wanted to engage with a black female professional because I felt like that kind of support would better allow me to resonate with their approach because that’s my lived experience.

I struggled to find that in the beginning. And then the third thing I was very visually aware of was the cost. I realized that I was in a position of privilege, like I had access to medical aid and medical care.

When I reflected on it, because I was not allowed to have my laptop, I had all the time to think about these things. I said, if I am in the space where I have access to this medical care, how are people navigating it if they don’t have the financial resources and access to care that I do?

And that prompted my journey around understanding first, if my experience was mine alone, or if it was a broader systemic experience, which I then realized it is a broader experience that people are just maybe not talking about, and not nearly enough attention is being placed or spotlights are being placed on mental health.

I then also realized that it wasn’t unique to my lived experience. Many people were struggling with mental health especially in workplaces, and they just weren’t talking about it.

Then I think the final straw that broke the camel’s back for me was losing a really good friend to suicide. And I think it really shocked our social and friendship and family community.

Because it appeared to be a person who was thriving, excelling, very sociable, in many ways similar to a lot of us who were also deeply affected by the passing. And that really prompted me or gave me a sense of urgency to start building in the space.

So it’s a very personal nexus that created this curiosity around what is mental health? Is it a systemic challenge? How urgent and severe is it? And how are people getting help?

I went through Pandora’s box when I struggled with my mental health journey then unearthed things that I didn’t realize were so systemic and so pervasive and so prevalent.

And that’s how the journey essentially began.

And this was pre-COVID. So I think about a year before, no, two years before COVID is not when I started building, but when I had this very visceral encounter and experience with mental health.

That created a sense of urgency. I quit my job soon after. And I went through a process of doing freelance work and I went through a crisis of identity, if you will, trying to figure out what it is that I would do next until I finally decided that I really wanted to build something that would have a material impact on mental health, optimizing mental health for people who need help.

At the time, obviously, I didn’t know what it would look like, what form it would take, but I just knew that it was something that had been placed on my heart to solve for. It was very difficult at the time because no one, hardly anyone was talking about mental health.

COVID really amplified a lot of existing mental health issues, but they weren’t not there. It just amplified and created an additional sense of urgency around what is essentially mental health in crisis, especially amongst young adults.

Read Also: “If Mercy Does Not Post it, I Know This News is Not True” – Mercy Obidake, CEO of MO Media

What were the challenges you faced in the beginning and how did you overcome them?

There are so many challenges that I not only encountered in the beginning, but continue to encounter day to day. But I’ll summarize it in a couple of ways. So you touched on something really, really important, which is the difference in how we as Africans approach mental health versus in the West and other parts of the world.

And one of the biggest challenges before even getting to funding and product development and the like. One was getting people to actually open up about mental health in general. It’s not the same when you do customer interviews and you do discovery and you do the like for other products.

I’m generalizing here, people are open to sharing, this is my pain point, this is what I’m struggling with, this it would be really nice if I could solve this. However, in the case of mental health, and on the African continent, people just were way more reluctant to talk about it.

So that made it really difficult to try and understand the extent of the problem and the nuances behind the problem. I think what I encountered very early on was that there are a couple of hurdles to having those conversations.

Because you can’t start building if you don’t have data and if you don’t have insight. I think one mental health was seen and continues to be seen as something that from a religious construct is demonic in many ways and in many circles in South Africa and I suppose in the rest of the African continent and maybe the rest of the world.

But there’s a strong narrative that mental health or people who are struggling with mental health are perhaps possessed or under demonic influence and that narrative is very strong in the African culture and African context.

What that then does is it minimizes and invalidates the lived experience of people who are struggling. And then what that then does, it further exacerbates the problem in some ways.

Now this is not to say that there isn’t value in spiritual integration, a spiritual practice integration in mental wellbeing. But it is to say that a lot of the issue stems from misconceived or misinformation and lack of understanding around what it is and what the root causes are.

Really understanding that in many spaces, this is a brain chemistry issue. And there’s a spectrum and we don’t need to get into the details, but it’s a brain chemistry issue in certain instances.

That is not something that can be over-spiritualized because if you have a brain tumor or if you have a tumor ulcer in your body and it comes up on a scan, the path is clear. This needs to be treated in this way. These are the different treatment pathways.

But because it’s a mind thing, if you will, it just leaves things open to so many interpretations. So that I encountered, just people rooted in not wanting to let go of that ideology that it’s a religious and spiritual problem to be solved.

The second thing is culture as well, which links to religion as well. I found that many Africans, again, generalizing, but talking about feelings and being vulnerable, especially amongst men, which is the whole topic in and of itself, but talking about feelings and being vulnerable was frowned upon.

So there’s a lot around, you’ll hear people talking about like the strong black woman trope. And it’s a real function of generations of forcing people to suppress their emotions, forcing people to prioritize pursuit of excellence above everything.

To prioritize securing the bag or to prioritize keeping your family together and all these things really created this rigid infrastructure that forced people to suppress and therefore not have vulnerable conversations.

And I’m speaking again from my lived experience as a black African woman and speaking about this unique context.

Then I think the third thing was really around people not actually even understanding what mental health is. And I think we will continue to iterate around what it looks like, what being mentally healthy and being mentally well look like.

You can be struggling with your mental health, but not have a diagnosable mental health condition. So what is difficult about mental health and solving in this space is that there’s so many layers and there’s so much nuances.

So I think just before even getting to the typical challenges that a founder would navigate around funding. It’s people not having an understanding of what mental health is, what mental health care looks like, what conversations need to be had, and what kind of points of understanding there need to be around mental health.

And so how do you then convince people that there’s a problem to be solved if people aren’t even having the conversations about that problem to begin with. Or if their frame of reference is something that is completely different to what your frame of reference is.

So a large part of what the initial challenge is the continuous, you know, what is in the DNA of Amari is education and building awareness and building understanding.

Because even in the business and organizational space, how do you sell the idea and the principle that investing in your employees’ mental health is something that will have positive business outcomes for you.

It’s something that anyone who’s building in the mental health space will tell you that it keeps them up at night. Because it’s not just talking about a feel good exercise that’s gonna sell the business.

Like I feel better because I’m caring for my employees. What’s gonna sell them is how much is this gonna cost me? How big of a problem is it for me to actually spend money on it? And if I spend money on it, how much am I gonna get in return? What’s my ROI gonna be? And that’s the conversation that is really a difficult sell.

But the main thing, I think, and anyone who’s building the space will talk about is the lack of awareness, the lack of understanding and how to map this problem, quantify it.

And package it in a way that it not only then says, okay, people will pay for this and they see the value in it, but also if they do, these are the tangible benefits and outcomes that will come about as a result of solving that.

It’s just sometimes I think to say to my friends, I wish I had chosen something a bit more, a bit more linear, you know, like, if you buy this, and you invest this, this is what you’ll get in return for sure.

But there are also indirect benefits that come from investing in your mental health. Not all of it can be quantified.

So it’s this tension between building for social good, like, yes, you have happier people, more productive employees, more connected and present fathers, mothers, friends, et cetera. Those are all great things.

By trying to tie it and align it with economic outcomes because you just cannot build a business on feel good. This is a social enterprise and it’s for profit and in order for it to be impactful it has to make commercial sense.

You talked about lack of awareness so what strategies are you using to create awareness about mental health?

There’s a couple of things that we are doing around awareness and it’s always iterating. The one thing that I realized is that people don’t know what they don’t know.

“You can be struggling with your mental health, but not have a diagnosable mental health condition.”

It’s very practically what I realized over time is that how do we create a tool or something that people can quite quickly understand if they’re struggling or if there’s potential that they’re struggling and that can be the initial entry point.

So we have a screening tool and we’re building more screening tools into our platform, which basically they’re all based on a standardized clinical format.

You are asked a series of questions, you then have a score that is assigned to you based on the answers you gave and that gives you a sense of where you might be.

I’ll simplify it, it’s like a depression scale. I’ll call it that. Please clinicians, don’t come for me. I’m just simplifying this with a depression scale. And it’ll say, let’s say for argument’s sake, it’s a score out of 10, which it isn’t, it’s a little bit more complex.

If you get 9 out of 10 or between 8 and 10, there is a high chance that you are struggling with severe depression and that can inform you. Because the information gap is that you don’t know that you’re struggling, you can’t put language to it.

So part of awareness is giving people those kinds of tools in their hands to say, oh, I didn’t know that I might be struggling with depression. It’s not a diagnosis. People will also tell, most clinicians will also tell you that. And we have those disclaimers, but that’s a starting point from an awareness perspective.

The second thing we do is we try to build thought leadership in the space. That’s one of the things that also keeps me up at night.

So in my own personal life and in my personal socials, what I realized is that if you’re not creating conversation or spaces to have or to create safe spaces for people to ask questions that may seem silly for argument’s sake.

Then you’re not going to understand where the information gaps are. So we’ve tried to do webinars, e-webinars and the like to really have as honest engagements as possible around mental health at the intersection of different things.

For example, founder mental health is something that I’m deeply passionate about, of course, as a founder myself and having engaged and engaging continuously with founders.

Founders are significantly more likely to struggle with anxiety, burnout and depression if you look at a couple of studies that have come out in recent years.

For various reasons we could talk about, but our idea is how do you essentially create safe spaces for engagement, for people to ask the questions that they may otherwise not be able to ask in traditional work settings or in traditional social settings.

The third thing that we try and do is also to create tools for people to quantify. I keep going back to quantifying because I realized over time that it’s difficult to educate people and create awareness, especially when you talk about decision makers in business and the like, if you don’t have data and if you don’t have numbers.

So quantifying, for example, on our platform, we have a calculator which basically shows how much you’re potentially losing by not investing in mental health.

And those kinds of tools and calculators create an awareness that there is some sort of problem and then the point of departure for people to engage from that lens. Like, oh, this my score shows me that I might be depressed. Tell me more about depression.

And so those things are things that we’ve tried to build in our infrastructure or that we built into our product roadmap and the likes. Because initially we did take the approach of posting about what depression is.

We will continue to do that. We can create think pieces around anxiety in the workplace. And those things are all great.

But what we’ve realized drives engagement is empowering people with tools, self-screening tools, calculators and tools to quantify the impact of what it is to be mentally healthy or to be what the implications are if you don’t invest in mental health.

The other things I think are typical things business owners would do, of course, we create blog pieces and we have all those things.

We try to engage with key decision makers in organizational spaces like HR and people leaders to better understand what their mental health challenges of their organizations look like and how we can solve those pain points.

And we do all those things. But I’ve realized in this five year experience that it’s very difficult to educate and create awareness if you don’t have data and if you don’t have ROI in your pockets to then begin the conversation.

Because people will say, why should it matter to me? And I keep going back to business because I suppose we can touch on it at a later stage, because our model is primarily B2B.

In the beginning, in the ideation stage, thought of direct to consumer, I want mental health to be accessible, so how can we put a therapist in your pocket? That was my very basic idea initially.

And then you quickly realize that there’s so many battles to fight before people can even access that support. It’s incredibly expensive. It costs on average 1,000 rand per 60-minute therapy session in the country, and that makes it inaccessible.

So what we then pivoted to how do we appeal to organizations to subsidize or cover the cost of access to our platform for their employees or their students?

And how we do that by educating them around the implications are if you don’t invest in mental health, what the implications are if you do, and constantly trying to figure out how we show outcomes.

And that is something that keeps me up at night. Obviously, we also have this space where we post about facts and what mental health is, but we really try to engage on a data-driven perspective.

Even with our clients, we really have shifted to how we create a repository of data for them to make data-driven decisions. It’s very different from how I initially thought about building a business.

I think I was quite disillusioned about wanting to like, how do you create happier lives? It was kind of fluffy. And then I quickly realized that, how can I quantify, like, how can I follow the money? This can be the ultimate outcome.

Read Also: We Have Provided 7,000 Women with Our Antenatal Services – Kobusingye Mackline

What led you into rebranding from The PocketCouch to Amari Health and what other services did you include to arrive at Amari Health?

We rebranded last year. And that was three and a half years into our journey. Initially, my idea was to create this direct to consumer teletherapy platform, which is essentially therapy in your pocket and that was a good starting point.

Then I realized that the opportunities were much broader in ways that led to a diverse nuisance. I’m just offering convenient therapy when we built this platform and we integrated mental health into the system that connects all these fragmented pieces.

So from this direct to consumer teletherapy platform, we then asked, how do we create a mental health ecosystem that allows for people to access mental health care support in a way that’s convenient, that’s culturally inclusive, and that’s cost effective?

And what does that entail? So on the one end, yes, it is therapy, but on the other end, it’s also empowering the self to better understand if they’re struggling. That includes the streets of integrated screening tools, which is by and large, our initial entry point for our customers.

So it gives them a diagnostic at a very high level. And in addition, you can engage with those screening tools over time and see in between sessions how you’re doing. What it then also allows for us to do is to track more closely outcomes.

We aren’t wanting to create access to therapy for therapy’s sake. We want to create access to therapy and mental health care support so that when six months down the line, you do your self-screening tool and you’ve been engaging with Amari, something has changed on the positive.

So we became a lot more data-driven and tried to be more data-informed. Another thing we started doing is integrating, creating our chatbot, of which the idea is how do you support people in between therapy sessions if they are opting for therapy, but also how do you empower people even if they aren’t getting therapy?

Empowerment looks like a couple of things. Education, which we spoke about, and awareness looks like affirmation, so how do you affirm people and get them to the place where they are vulnerable or they feel not being vulnerable to seek out help.

“…If you’re not creating conversation or spaces to have or to create safe spaces for people to ask questions that may seem silly for argument’s sake. Then you’re not going to understand where the information gaps are…”

So I think I realized in it that it was not just about, it was no longer just about access to therapy. It was solving for this fragmented ecosystem which is a function of creating awareness, which is a function of the providers, people who help to create an ecosystem of support.

I think as a second thing, cultural inclusivity is so important for us at Amari. Essentially, I suppose because it’s a home-based solution. So we are in a country, in South Africa and you obviously have a different lived experience,but you can speak to how diverse the country is in and of themselves, not the continent.

It’s definitely not as homogeneous as people like to present it. But even in the country itself, there are cultural nuances. We have 12 or 11 official languages in South Africa.

When you think about something as personal as mental health, you don’t want to exclude people from getting support because they can’t engage in the language of their voice.

So with the platform, you can connect resources and expertise to those who can speak your language. And so currently, we have about 80 % of the South African languages who can speak your language.

In addition to the tools that we are building, now how do we shift those tools so that they’re not English focused. They’re also covering language that people can engage with the whole ecosystem in a manner of their choice.

Then the final element is also we realize that catering for context, unique South African context also means adjusting your mindset. So we’re now building a hybrid approach, which is the mental healthcare ecosystem.

Where we are the digital partner, but now we’ve integrated the medical facility, which is the medical facility that we’ve built with my mother and my sister, to say, people who are looking for in-person support. Is there a way for them to do that?

As their journey is not just platform specific, you know, engaging on the platform. If they really need and want to see a therapist in person, how do we allow them to do that?

Because the context is different. If you have an 80 year old grandma who wants to engage with a therapist not only in her language. But with the therapist who you can touch and see and feel.

Is it really fair for us to be exclusive, exclusionary in that regard if we can service that person in person?

So in a nutshell, Amari represents more of a fundamental revolution of our human approach, which is largely around holding something that is not only uniquely African but that also speaks to the broader spectrum of mental well-being and not just agronomy.

We wanted a name that then becomes synonymous with mental health and access across the continent. It also stems from means, bravery, and courage. There’s a lot of arguments about what Amari actually means.

How did you structure your business so that the mental health of your team is taken care of and how are you using this structure to help entrepreneurs with the mental health of their employees?

It’s a very good question and it’s two ways to answer the question. So on the one hand, by virtue of building a startup uniquely in the African context, as a woman, as a black woman in a very underrepresented tech space, almost requires a lot more. How can I put this?

You are breaking barriers and you’re knocking on doors that you were originally designed for you not to knock on. And to bash them through it requires working really hard and working differently and pushing the needle.

So I would say for me as a person as a founder I don’t always practice what I preach. That’s my most vulnerable answer.

I’m constantly trying to hold myself to account in the sense that I should be working when I am having dinner or I should be creating space for me to take breaks throughout the year.

Because you don’t have someone holding you accountable to taking vacation by yourself as a founder. So I’m not so great at it for myself. I am trying to put boundaries in place. When it comes to my team, it’s again a very lean team, so it’s still evolving and then in and of itself, it’s a lot of pressure.

I think as a leader, I try to connect individually with people as often as I can. And I also try to be vulnerable about where I’m from. I will just say, I am having a nightmare of a week. Yeah, really going to be difficult for me to respond to. I think I try to be quite personable.

And I try to be open that people can be vulnerable to their fates. What I’m trying to do is find the quick way for how people can engage with each other and with me and the need that’s vulnerable. I think that’s too many obviously apart from providing access to therapy and therapists as part of the benefits.

And I try to find more of what I would want in an organization five years ago. What was lacking, what was really lacking for me was not feeling like they were safe spaces to express what I was struggling with and not feeling like I could be honest.

And for a long time building it, I’m taking time off for me to go to the academy. It was very gray because I didn’t know how I was going to receive the fact that I’m taking time off because I’m burnt out.

I try to be honest about what I’m trying to do and I think that’s where it starts for me and the rest of the organization. And I also manage my own page.

I can work late at night between 2 a.m. or productively, whereas my house may have a pretty productive worker between 5 a.m. and 4 a.m, and 10 a.m. And try to be adaptable as a founder as possible.

I work with it. What I want to do, especially as a founder in the blockchain space, is to be an epithet list of what you’re searching for. So it is something that I try to be very kind to. In some ways, I think, as a founder myself, I work with the care of my own mental health and I am vulnerable about that.

It requires my team, my community, my resources, access to it. I do that and for example, I come from a family of doctors. A lot of them are not as adherent to their medication as their patients think.

My honest answer, I’m not doing a really good job right now for myself, but I will try and hold space for my kids and the people around me.

Read Also: Helping Students & Entrepreneurs Sell Online More Efficiently – Edgar Odey

When you were starting your business, how did you raise funds?

Funding was a very difficult landscape to navigate. And I think for me, it was largely self-funded. What I did after I quit my job, would not advise quitting a job unless it’s untenable in play.

So saving at least four months worth of salary if possible. I know it’s heavy and I’m speaking from a very private perspective anyway, but that was not the best idea. But what it did force me to do is I found freelancing consulting work that I was doing and trying to build the company.

And it was likely self-funded. I’m glad that I had family and friends around. So we’re not in a political, money-esque type of environment where I have an uncle who would give me a cheque because of the idea I had of giving myself more happiness in the world.

And so it was a largely self-funded family and the people who were basically helping me find the right place. My partner at the time was in formal employment and was very supportive of the vision. So I had the experience of doing that stuff.

But it was not for self-sacrifice for a really long time. And I was lucky enough to to be a part of a network of community and that’s the importance of community and building resilience.

Advice for people, especially women starting their business

To all the women embarking on their entrepreneurial journey, my advice is simple: believe in yourself. You have the strength and vision to make your business a success. Understand your ‘why’—this will fuel your passion and guide your decisions.

Be adaptable because things won’t always go as planned, and that’s okay. Learn from your challenges and keep moving forward. Build a network of supportive mentors and peers who lift you up, and don’t hesitate to ask for help when needed.

Trust your instincts, especially when it comes to your business and your customers. And don’t forget to be financially savvy—know the numbers, as they are the backbone of your business.

Finally, prioritize your mental health. The entrepreneurial journey can be demanding, but remember to take care of yourself along the way. Celebrate each small victory because every step forward brings you closer to your dream.

Most importantly, stay true to your values and let nothing—especially gender biases—hold you back. The world needs more women leading businesses, and your success will inspire others to follow.

Contact or follow Onkgopotse Khumalo

Leave a comment below and follow us on social media for update:

- Facebook: Today Africa

- Instagram: Today Africa

- Twitter: Today Africa

- LinkedIn: Today Africa