Adanne Uche, founder/CEO of Ady’s Agro Processing Limited, started her entrepreneurial journey not with a grand plan, but through restlessness, experimentation, and a strong desire to stay active while raising her children.

A graduate of Foreign Languages and Literature from the University of Port Harcourt, she ventured into business after the birth of her first child in 2012. Her first three businesses began with passion but ended due to a lack of structure, sustainability, or shifting market trends. Despite the setbacks, she kept moving forward.

In 2016, she founded Ady’s Agro Processing, a nutrition-based food processing company in Lagos. What started as a simple shopping service for friends evolved into a business addressing real gaps in the market, offering healthy, preservative-free local ingredients.

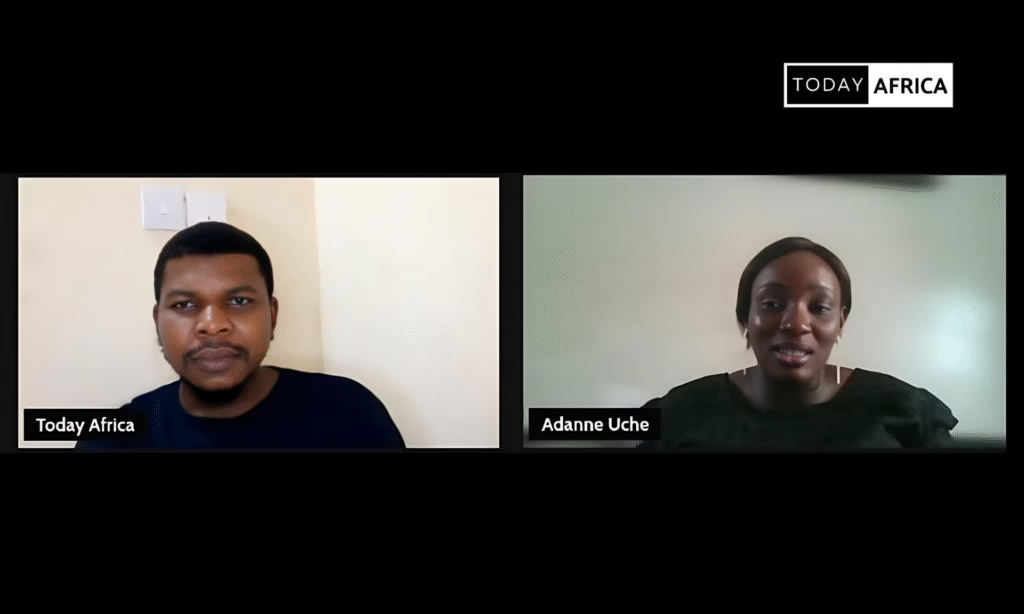

In this interview with Today Africa, Adanne Uche opens up about her entrepreneurial journey – sharing lessons from failure, navigating cash flow in Nigeria’s tough economy, uncovering market needs by simply listening, and how women can build lasting brands starting with nothing but their name and integrity.

Tell us more about yourself

She introduces herself: “My name is Adanne Uche and I’m the founder/CEO at Ady’s Agro Processing Limited.” A nutrition-based food processing and packaging business, based in Lagos, that provides families with healthier cooking ingredients.

But behind the name Ady’s Agro is a woman whose journey has been anything but simple.

A graduate of Foreign Languages and Literature from the University of Port Harcourt, Adanne is not your typical agribusiness entrepreneur. Her education wasn’t in food science or supply chain logistics.

Yet her business thrives, because for Adanne, entrepreneurship isn’t about background; it’s about resilience and relevance.

She juggles the demands of business with the rhythms of home life. “I’m married. I have four children; two girls, two boys, and I’m from Abia State,” she says.

Could you tell us about your two failed businesses and what kept you going?

She laughs and says there are three failed businesses. The first one started when I had my first child.

“I always want to do something. I always want to help,” she recalled with a soft laugh.

It was 2012, and she had never run a business before. But with her savings, she imported nursery décor and began marketing online. Her first customer was a foreigner living in Ikoyi.

She traveled across town to decorate a child’s room herself, having never done one before. It was a thrilling experiment. Soon, she branched into children’s event planning—an industry virtually nonexistent at the time.

She was learning, hustling, employing staff, and even being mentored by one of the only known names in the space, Mr. Tijan. But the business eventually collapsed. “There wasn’t a strategy. There wasn’t any document. Just so passion.”

Two more failed businesses would follow. One in catering—selling homemade lunches to office workers, and another in beddings—where she opened shops in Oshodi and Lagos Island, only to shut them down as life changed.

“That was just business because I was selling and making money. But I didn’t see a path on that route,” she said. “There’s a difference between a business person and an entrepreneur.”

Read Also: How Olamide Ilori is Building Africa’s Fintech Future Through Front-End Engineering

What kept you going after the failures?

“I’m the only one that has business acumen in my house,” she stated matter-of-factly. Where others saw impossibility, Adanne saw opportunity—in traffic patterns, in household inefficiencies, in the chaos of traditional markets.

When she and her husband moved to the island, she began shopping on behalf of friends. “They said, okay, sure,” she remembered. She started with six families. It was a simple but profound insight: people lacked time.

Growing up, her mother never went to the market herself. She called vendors to deliver. That memory, combined with her love for bargaining, pushed her to test the waters of grocery and ingredient sourcing.

And in the market, she noticed something disturbing. “I saw firsthand the heavy adulteration. You don’t even want to know what goes on.”

That sparked the real fire. If families needed healthier, safer, and more convenient options, someone had to build it. In 2016, Ady’s Agro Processing Limited was born. By 2017, she knew: this was it.

Wait it the need that sparked your conviction?

“It was the need,” she said simply. What started as grocery shopping evolved into sourcing and processing. The deeper she went, the more broken the system appeared.

“Even if you’re not buying from me, read the ingredient list,” she warned. She speaks often, and fiercely, about the dangers of adulterated foods.

“Africa is blessed. Why should I import what we grow here, processed abroad, and sold back to me?”

What are the trends shaping the food processing industry right now in Africa?

“Healthy nutrition,” Adanne answered instantly.

COVID-19 changed everything. Suddenly, ingredients like ginger, turmeric, and garlic were essential. “People now intentionally just get ginger, pound it, and start chewing,” she laughed.

And then there’s technology. Chinese companies bombard her with emails daily. Machines, software, innovations. “Technology is everything now.”

Consumers are more informed. They’re paying attention. And Ady’s is riding that wave.

How do you ensure that your seasoning blend is preservative-free in a hot environment?

“Processing. That’s our unique selling point,” she said.

From fresh onions to ginger, everything is washed, cut, dried, and blended in-house. No shortcuts, no outsourcing, and no chemical preservatives.

“We do triple capping to lock in moisture. First sealing, second sealing, third sealing. Even though it’s expensive, it’s how we maintain quality.”

Read Also: Why Atamelang Free Said No to a 9–5 and Built a Skincare Brand Instead

Tell us about your product line

Ady’s started with three basics: palm oil, crayfish, and fish. Today, the company boasts over 21 product lines.

There are single spices (cinnamon, ginger, turmeric, garlic), seasoning blends (jollof, fried rice, pepper soup), gluten-free flours (sweet potato, acha), herbal teas, honey, and oils.

“People were using spices for tea. So why scoop from a jar when you can dip a teabag?”

What was the biggest challenge going from local to global?

“Getting buyers,” she said.

African stores abroad often purchase in bulk, then rebrand the product. “It doesn’t give us much platform to push our own brand.”

She advocated for variety in stores. “Imagine I open a supermarket and everything is Ady’s. You are just boxing them.”

The export community, she added, is frustratingly secretive. “Everyone is hoarding information. I say, the sky is too big. You fly, I fly.”

How did you get your first 100 customers?

“Friends and communities,” she said.

While Instagram and Facebook helped visibility, sales came from tight-knit groups. Relationships mattered more than algorithms.

How has customers’ acceptance differed abroad with the one you have here in Nigeria?

“Before, people were proud to buy foreign,” she said. Not anymore.

“Being foreign doesn’t mean quality.” Today, customers value freshness and authenticity. “They now know the raw materials come from here. They prefer to patronize local brands.”

How did you finance your scaling from kitchen to factory to export?

She began humbly. A N30,000 loan from her brother. Three gallons of palm oil. Then a loan from the Central Bank of Nigeria, followed by two grants in 2021.

“That was what propelled me out of the kitchen.”

Today, Ady’s is sustained through a mix of loans, grants, and product sales.

How do you manage cash flow in a tough economy like ours?

“It’s tough,” she admitted.

“Especially for agri-business.” Ady’s strategy is product diversification: “There are some products that are doing well, there are some products that are not doing well. So some of them are seasonal, some of them are not seasonal.”

The company also provides services like white labeling and contract manufacturing.

Read Also: Startup Stories of 16 African Entrepreneurs We Interviewed

You work with U.N. Women and Catalyst Now, which is based on your role as a founder. What advice do you give to women who want to build their brand?

“Start with yourself. Build your personal brand.”

Adanne teaches brand building in workshops, and her message is clear: trust is everything. “If I trust you, I can buy from you.”

She draws a firm line between her personal and business brands. “Ady’s is Ady’s. Adanne is Adanne. There are things I will do on my personal page, but not on the business page.”

Her final word? Guard your name.

“You can do anything else to me, but my name? I protect it with everything.”

What does gender-responsive procurement mean in practice, and how did this policy affect your growth?

When Adanne Uche speaks about gender-responsive procurement, she doesn’t sound like she’s quoting from a UN manual. She’s lived it, breathed it, scaled her business with it.

“I mentioned how people that know try as much as possible to hoard the information that they know,” she begins, with a pointed honesty that cuts through pretense.

“But thanks to technology, everything is there. I can kick and find it. I can ask somebody, even if you don’t want to, I will go there and look for it.”

Her entry into the world of procurement wasn’t accidental. It came through programs championed by UN Women and UPS, where she was not only trained but onboarded into a network that had, until recently, been overwhelmingly male.

“They are saying that more than 90% of the people who do procurement are men,” she recalls. But that statistic didn’t scare her—it motivated her. “Thanks to them, they are trying to give us awareness, give us the tools through the UN Take Action.”

Through these initiatives, she gained the certifications she once thought were distant privileges of an elite circle. “Now I have all the certifications that I need to actually bid for anything I want to. They also helped us register on the platform.”

She ticks off her credentials like someone who knows exactly what they’re worth. Lagos State procurement platform. UN platform. She’s not just signed up—she’s ready.

“It’s actually helped us as a business,” she says, but she doesn’t stop there.

“We need to empower each other,” she says plainly. “And I keep telling them, the area of competition is common. Yes, there’s the healthy competition. We can be in the same business, and we do have the competition.”

There’s a moment that crystallized it all. A procurement team visited her store. They were skeptical at first, glancing around the modest space. “They were looking, oh, this place is small,” she recounts.

But then the questions came. The paperwork. The documentation. The hard metrics that separate contenders from the rest.

“I was just bringing out documents—financial documents,” she recalls. “And they said, ‘Wow, ma’am, you are actually prepared.’”

Her response was firm: “Yes, that I’m a small business does not mean I won’t be prepared. I have all those things. So you call me, I’ll bring it. My tax on point, everything on point—because you never know.”

“You can’t be responsible if your documents are not in place, if your finances are not in place, if you are not paying taxes.”

How big an impact does Ady’s Agro have on local agriculture?

In Ady’s Agro, waste isn’t waste. It’s raw material, it’s possibility, it’s part of a closed loop that fuels a local agricultural ecosystem.

“We clean the crayfish, the shaft from the crayfish—we give it to fish farmers. They use it to feed their fishes. That’s zero waste.”

The palm tree, Adanne explains, offers perhaps the most perfect metaphor for her approach to agriculture. “There’s no waste in palm oil. From the shell to the kernel to the branches—everything is needed. That’s why the Bible says you’ll be like a palm tree.”

Even the bottles that don’t meet quality standards are handed off to recycling companies. “They give us money, they recycle it, and reuse it. So we try as much as possible to do zero waste.”

One of the most innovative outputs? Bullion cubes made from fish heads. “The fish head that you throw away—we clean it, dry it, grind it, and use it as seasoning. People don’t know.” She leans in. “But we do.”

Read Also: Peter Browne on Using Tech, Faith, & Innovation to Empower Emerging Farmers

Packaging in Nigeria is a challenge. How did you solve it and why does it matter for food safety?

Adanne’s journey with packaging began at a supermarket shelf, where her preservative and additive-free product was mistaken for just another jar of spice.

“They said, ‘Ma’am, your price is expensive.’ I said, ‘Because of the processing. It has no preservatives.’ They said, ‘It’s the same bottle. What distinguishes you?”

That question led her on a quest that took her to Kano, where she commissioned a custom bottle mold.

“You won’t see that type of bottle on the shelf,” she says proudly. “It is very expensive.” But when the mold broke, repairing it became another lesson in adaptation.

“We had to look for another size of bottle. So now we have a particular bottle we use for exports, and a different one for local.” It wasn’t planned—but it was necessary.

Adanne introduced a refillable pouch system using recyclable paper. “It makes life easier.” And safer. In Nigeria’s often chaotic packaging industry, such foresight is critical.

“I understand manufacturers need to be profitable. So you see them saying minimum order quantity, 10,000 or 30,000. As a small business, do you have that amount to just plug into packaging?” she asks, then answers herself: “But in the long run, it’s worth it. It’s safe. It saves cost and time.”

What was your first major investment—machinery, packaging, or branding—and why?

It wasn’t the branding. Or even the bottles. It was a humble, grant-funded dehydrator. “A small dehydrator,” she says, “but it came as a grant, and it was the game changer.”

Even today, when her industrial machines are down, that original piece of equipment runs reliably on a small generator. “It’s really worked for me,” she reflects. “And I’m thankful to the grantor. It’s made a difference.”

Is your recipe guarded like Coca-Cola or could anyone just copy Ady’s magic if they had your ingredients?

“Spices are easy to copy and not easy to copy,” she laughs.

The story that drives the lesson is painfully clear. A young friend once asked Adanne to create a custom spice blend using her own ingredients. Adanne obliged. The friend’s customers loved it.

“One month later, she launched her own spice business.”

Now, Ady’s Agro doesn’t play. NDAs. Non-competes. Strict coding systems that change daily. “Even as a staff, you will not know how to do it. That’s how we maintain our recipe.”

She recently completed an international course on intellectual property. “I learned a lot. Now, we curate with caution.”

Read Also: Ayoola Ogunyomi on Bridging the Investment-Exit Gap in Africa’s Startup Ecosystem

What’s more powerful in Nigeria’s food business—perception or substance?

“Substance,” she says, without hesitation.

“You can perceive that a brand is good, and test it—and the brand is not good.” She’s blunt: “Perception is just peripheral. It can fade. Substance cannot.”

Still, branding matters. “People eat with their eyes before their mouth.”

Through a Global Alliance on Proof Nutrition initiative, she’s learning how to better position her brand. “There has to be something that distinguishes you—either in the packaging, the ingredients, whatever. We need to be different.”

She’s even thought about color theory. “Colors that are identified with food businesses—green, yellow, red, white. White is purity.”

You mentor over 400 youth and women. What do they ask you the most?

“They always ask how I started. And how I manage the business with my children.”

The answer? There’s no balance—just strategy.

“I have four children. During holidays, I don’t take them to extra classes. They come to the office and see the process.”

Her influence? Asian films. “They always go to their family businesses to learn. I want to imbibe this culture in my children. Ady’s cannot die with me.”

Read Also: Why Fana Haregot is Building More Than a Business, She’s Building Hope

What has been your toughest decision as an entrepreneur?

“Moving,” she says quietly.

Ady’s Agro is relocating to a larger processing facility. The decision, she admits, wasn’t easy. “We had to go to the board. Are we going to move? Is launching a single-use sachet a better idea? The money was huge.”

But they moved. And before that? A loan. “You hear all sorts of stories about loans. I thought they were scammers.”

Then one day, her banker called. “They said, ‘Madam Adanne, come and take this loan.’ I said, ‘What’s the interest?’ They said 20%. I said, ‘Ah, but I have 5% now!’”

Still, she took it. “And that changed the entire story. It helped us procure most of our machines. It actually helped us.”

Where do you see Ady’s Agro in the next five years?

“In the next five years, we’ll be the top nutrition-based food processing company from an Igbo woman,” she says with clarity and conviction.

She wants Ady’s Agro in hospitals, recommended by nutritionists. She wants families, both urban and rural, to use her zero-salt, low-sodium, MSG-free products. “We want to create change in the agricultural processing value chain.”

How do you plan to achieve all these?

“One step at a time,” she says.

They’ve already moved into a larger space. Next, they want MANCAP certification, UNICEF endorsements, and NGO partnerships for their baby food blends.

“It doesn’t happen in a day. But with the right partners and right connection, there’s nothing we cannot do.”

If a 16-year-old girl walked into your factory, what do you hope she sees and hears?

“I want her to see that every girl’s vision is valid.”

Ady’s Agro is proof. “A full-fledged processing company by an MSME that is doing well.” The message? “Your purpose, your vision, your dream—it is valid.”

Read Also: How Christopher O. Fallah Empowers Liberia’s Unbanked & Offline Citizens

What advice would you give to other women who want to start their business?

“Don’t do it alone.”

Her first three businesses failed, partly because she didn’t have a mentor. “You can’t do it if you don’t have somebody who has done it holding your hand.”

Her second piece of advice? Network. “The right network is more important than money. The right network opens doors.”

And her final word: “Your vision is valid. But do it right. Have a clear path, a clear vision. It will help you. Because when you sleep and wake up, you’ll remember—‘I want to be big. What’s the next step?”

Contact or follow Adanne Uche:

Leave a comment and follow us on social media for more tips:

- Facebook: Today Africa

- Instagram: Today Africa

- Twitter: Today Africa

- LinkedIn: Today Africa

- YouTube: Today Africa Studio