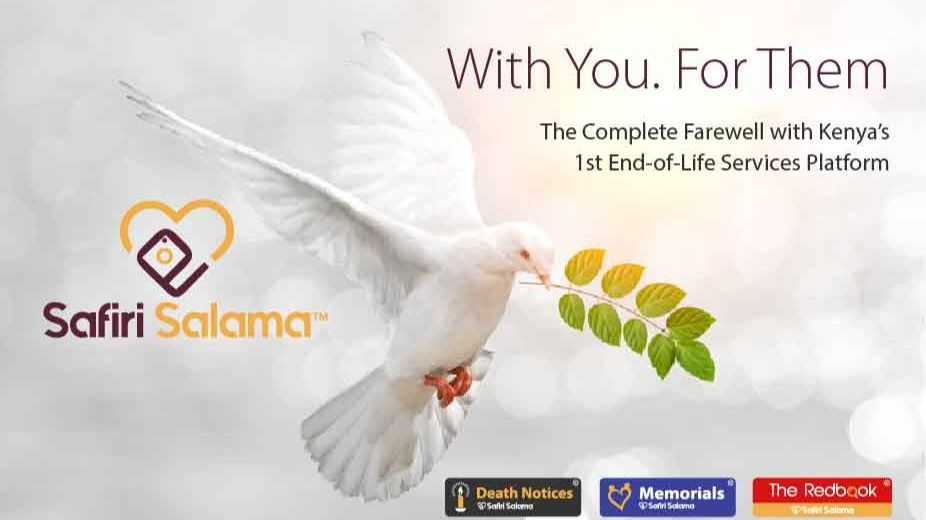

Death is hard and expensive for those left behind. Safiri Salama, a death tech startup is disrupting all aspects of death in Africa with end-life-services. This includes, will writing, planning, funerals, inheritance of digital assets, and human composting.

You understand that death is a sensitive topic in Africa and all over the world. But isn’t it a part of life? We think and talk so much about our future and plans for it, and death is also a part of this future. It’s okay to talk about death and make some arrangements for it during life. It’s even prudent and caring towards your beloved ones — to think about them coping with your death.

Whether experiencing grief after the unexpected death of a loved one, trying to plan a funeral with an ecological bent, or wanting to have a say in how we are remembered, Safiri Salama is innovating what happens after a loved one dies — and before you read, check out part one of this interview.

Can You Share Insight on How You Were Able to Raise Funds for Safiri Salama?

One of the things that we are going to confront very soon in Africa, it’s the funding models that we have for startups and which startups attract the most attention. Somehow, well, I’m not complaining, or maybe I am.

We managed to raise our first $100,000 to actually complete the prototype from an angel investor. But the angel investor was a person, a Kenyan, who was known to us, who has settled in the US. And so was able to rally together some funding for us to actually do the prototype. And because they understood the culture and they understood the need. It was easy for them even before the entire thing was out to actually figure out this is going to be important. We in the diaspora pay for a lot of funerals back home.

How do we actually know that the money we said is used for the correct purpose? How do we identify the suppliers that we need and how do we circulate the information on social media? But the problem that’s about to happen and which has been happening. But now it’s becoming critical that a lot of the funding that will go to startups in Africa would actually reflect the biases of the investors. The same way donor funding in Africa is done, it actually many times reflects the biases of the donor, in the sense of they use existing models, what they know.

So you will figure out that 80%, possibly 75% to 80% of the entire funding to Africa startups, as much as it reads on paper very nice, lots of hundreds of millions of dollars. Most of them will go to fintechs because the story within the West and in Europe is that Africans are trying to find new ways of trading and paying for services. And so fintechs are the place to go. Now that creates a different problem because in Kenya now we have over 50 fintechs, which doesn’t make sense. Because how many fintechs can one economy really absorb?

And so you have a situation like Kenya where Safaricom and M-Pesa. M-Pesa basically is the biggest fintech that we have across this region. And over 98% of Kenyans use it. You pay bills, you pay for utilities, you pay for school fees, whatever it is that you want to do. You send money, you receive money, you fundraise, whatever it is you’re trying to do, you can do it through that. However, now there are niche fintechs that have appeared all over, many of them replicating each other. But the donor funding, or rather the investor funding seems to go there.

So this whole aspect of having tech affects or creates the social impact platforms that will revolutionize a couple of other areas in Africa. Let’s say the funeral industry in Kenya could be worth possibly about five to $600 million. And that’s a very conservative estimate because there are hundreds of services, but they are not documented as belonging to an industry. You end up with a situation whereby since it’s a gray area, you have a challenge with fundraising. So our initial bit after doing the initial angel fundraising, we are going into pre-seed fundraising, but it is becoming a tasking exercise to actually explain to a lot of investors who cannot visualize that the funeral industry is actually one of the country’s biggest.

So what we’ve decided to do is actually to say let us go on revenue mode. We are working to actually raise our own revenue by executing different ways, working with different funeral homes, getting some funeral homes to be pre-sellers or resellers of our services and stuff like that. There’s a couple of things we’re implementing, including which other areas do we delve into.

There’s funeral insurance, which is mostly static. But you hardly see very innovative funding or insurance services that are in the funeral industry. So we’ve decided to go on a revenue model, especially this year, to try and actually make a much more convincing case.

Technology is Evolving Rapidly. How Do You See Technology Shaping Your Industry and How is Safiri Salama Planning to stay Ahead in the Death Tech Industry?

I think technology may be evolving. But I think the first thing we have to recognize is that the needs are the same. People need to grieve for their loved ones. What is now happening is that one, we are on a timeline. Well, unless you’re in Ghana, where a funeral will take four, five, six months.

Across the rest of Africa, within 10 days a person has been buried. This place is an enormous strain on a family. And you have to remember, funerals being the biggest rites of passage actually now demand a lot. One is about family and pride. And you’ll find it doesn’t matter what kind of income families try to put their best foot forward when it comes to organizing a funeral.

What is actually to be focused on are the needs. The need is about time. Technology helps with the issue of time in terms of sourcing what you need. That is why you are able to actually do your entire shopping from your house. If you have an e-commerce platform next to you. So in terms of time and the pressure of actually doing buries within a specific time, that will happen. So technology will shape that by making the services more competitive.

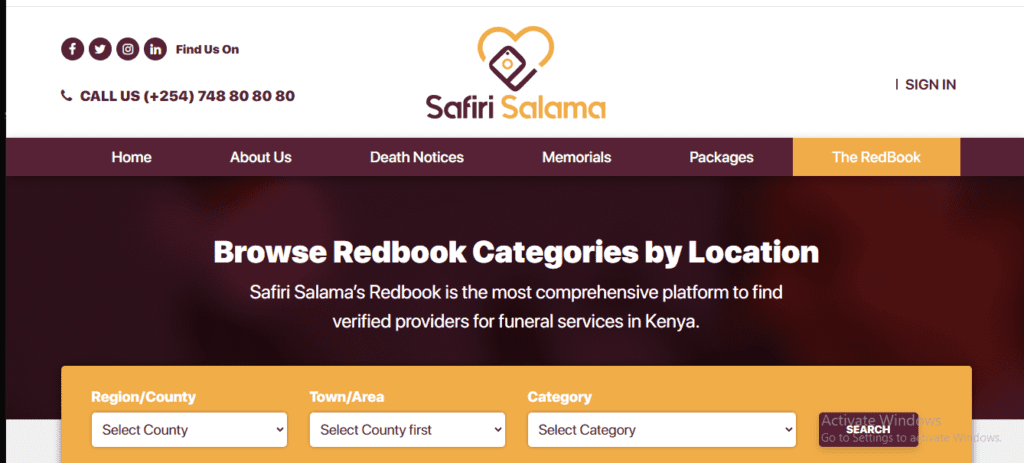

You no longer have a few funeral homes who never declare their pricings. You no longer have few services. I mean, if you ask a lot of people, what’s the price of a coffin or a casket? They wouldn’t know. And the reason they wouldn’t know is that the companies that offer these services have never felt pressured to put out their products and the costs of those products.

Now, across Europe, there’s a movement right now to force funeral homes and funeral directors to be fair to people when they are bereaved. Because of this lack of information, people don’t want to talk about that. But when somebody dies, they’re helpless. They don’t know much about what to do. This hands over the power to funeral homes and to funeral product suppliers, which means whatever they charge you is what you pay. Now we are having consumers who are questioning more, did I get a fair deal? Was I taken advantage of?

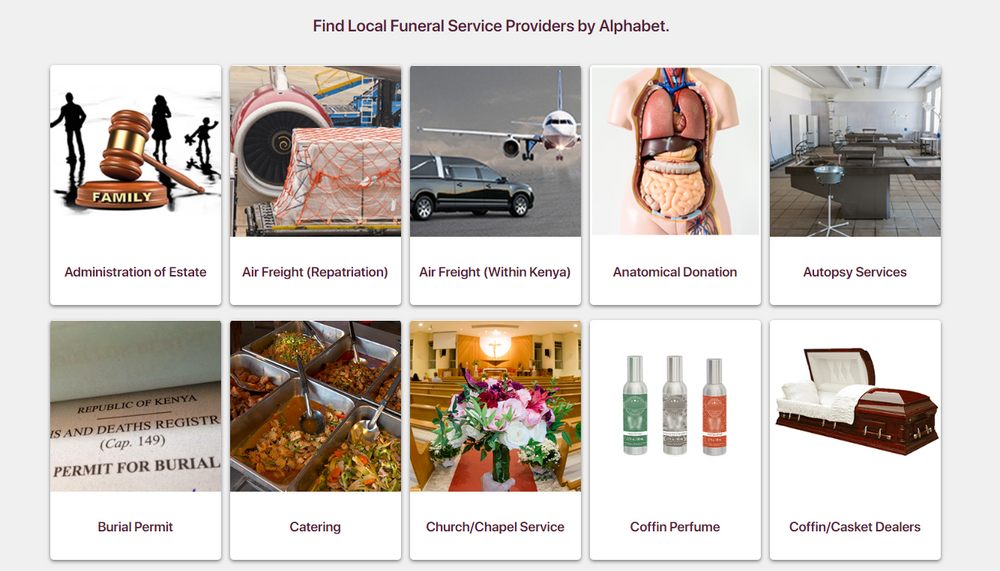

Technology will help solve that because what we have on Safiri Salama now, if you go to our Red Book and you check, let’s say the coffin section, people actually now have their pricings there, which allows you to compare. This wasn’t there before. You can compare flowers. You can compare a couple of services. And you can compare mobile toilets. We are actually encouraging funeral homes to also put in their prices, even if not exact, but say from this range to this range is what they charge. A house, how much is a house? Nobody seems to tell you that, unless you stumble on the first guy you talk to, he gives you a price and you have to pay.

And then what technology will do, it will force suppliers to be, one, much more robust in how they present their products. Previously, we’d just send you a couple of pictures on WhatsApp. And you figure out whether it’s in a dark corner. Just figure out, pick up something. And what is the price? We’ll tell you the price. Who do you compare that price with? Two, it will open up. Technology will also open up the communication around the subject of that. One of the things that leads to exploitation and sometimes unfair treatment of bereaved families is a lack of information.

And there is nobody advertising a service. There is nobody explaining to you a package that you’d have. There’s no funeral director. You have to stumble around as family members to figure something out. Technology puts out this product just like an e-commerce platform and enables people to actually discuss them. The good thing about that is that technology enables consumers to become more demanding, and that puts pressure on people who supply funeral products to be much more accommodating.

Then secondly, there is the issue of suppliers being much more competitive in their pricing. That’s what technology will force. A third, there is, we’ll have to go out of our way. I mean, you’ve seen the Ghanaian coffin industry. They’ve got very dramatic coffins. I mean, I’ve seen that. I mean, they will get the shape of a car, the shape of whatever else, the house or something like that. We look at it when you’re in Kenya with a lot of fascination like, wow. But even then, it is not a widely discussed subject. But imagine if you could actually go to different platforms where services are.

What is embalming? Very few people know what it is. And so when you go to a funeral home, you’re supposed to indicate whether you want your person to be embalmed or not. But right now, whatever you are told is what you’ll do. So what technology does, it provides us with more information and enables consumers to be more demanding, be more understanding, and then express their preferences. But the other thing that it will do is to create more products for people.

I’ll give you an example. We normally treat people who sell coffins as witches or whatever it is that they do. Now, what we will be doing is formalizing the death economy. And I know lots of people may take offense to what I say. I actually call it a funeral industry. I went to another funeral home and they said, you are the first person who has used the word funeral industry to us.

What technology will do, it will enable a lot of more people to invest in that industry which will make it more competitive. If it’s okay to actually sell more funeral flowers, make classy coffins. And this becomes something that is talked about. What it allows is more people to come into that industry without the stigma that the society attaches to them.

Considering Your Background in Communication and Brand Strategy. How Do You Approach Marketing Safiri Salama to Ensure Both Widespread and Sensitive Representation of Your Death Tech Services?

As someone who headed an advertising agency before and also worked on a lot of brand campaigns for different clients. One of the things that Africa suffers from is lack of homegrown brands. And I remember this was a subject at one of the first world economic forums, actually the first one economic forum to be held in Africa, which was in Cape Town and which I attended.

The issue that came up is that out of all brands that are in Africa, less than 5% are homegrown. Africans love good brands. And one of the things that has happened since then is that we now have a lot of other things other than just multinational brands. We actually have a couple of home brands growing from homegrown manufacturers. Our approach has been to create a brand that people can relate to. So brand development for us has been important as a brand which can be trusted and which can be felt, and which is presented in a way a mainstream brand can be presented.

So how are the products presented? What is the look and feel? What are the stories that you tell about this brand? Do we do audience surveys to understand? Because we’ve been out there and we figured out there were biases which were either feelings or biases which were that are custom oriented or culture oriented, you have to adapt to them. And that’s what our background enables us to do. We approach it like the way you’d approach a brand. Then you have to look at it as behavior change.

Communities will plan funerals. And at that time, no expenses are questioned. I mean you’d be a cheapskate and you’re a terrible person if you even try to negotiate about a coffin or question if the price looks unreasonable. What to do is to study that and engage behavior change campaigns to actually change a bit of that. It is okay to ask the price of a coffin. And if you find it unreasonable, it’s also okay to check the competition. It doesn’t make you a bad person.

And then continuous product improvements. What we have in the market, one common thing because we just have death notices like obituaries, which are static, both on radio and on TV and in the newspaper. Our whole idea is how do you make them much more robust, much more shareable on social media, and much more interactive. Allow people to leave TVs, allow people to lay a flower or light a candle, allow people to tell their own stories. Because Africans are good storytellers, just give them a platform to do that.

So the biggest thing we’ve learned is we have to create a brand that is appreciated and that engages people at an emotional level and that creates interactive products. So what we’ve learned from other products is what we really need to deploy here. I mean, it is terrible that you would create a very flashy wedding program and the same person created the worst funeral program with the worst pictures, not cleaned up, badly told stories. The appreciation of what consumers are saying is, I want quality, I want trendy, I want respectful. We need to deploy that to this industry. And that’s what we bring, having worked in a brand building environment.

What are the Strategies You Have Employed to Ensure that Safiri Salama Remains Both Convenient and Affordable to Your Customers While Maintaining a High Level of Profit in Your Revenue?

We have just gotten into the revenue stage. We are one year into the beta version. It took us about two to three years to develop this platform. One of the things is that a digital platform, what it does, like print media, radio and stuff like that, is that it actually allows you to price them cost-effectively. While I’ll give you a contrast. The smallest obituary in our mainstream newspaper, our leading newspaper, is about $200.

In contrast, Safiri Salama’s death notice is $20. So you can see what the contrast is. $200 for the smallest obituary you can get in a newspaper. And in our case, we are charging $20 for a death notice that you own, you can continuously update, you can share across social media platforms.

You can put in several other links and you only pay once. So price is going to be important with regard to that. Secondly, the cost on board is very simple. And then we had to make it mobile phone friendly. In Kenya, the mobile phone penetration is about 130%, meaning we have more mobile phones and people.

So, compared to readership of newspapers and TV stations and radio stations, online consumption has become the biggest conveyor of information. And so we’ve made it simple. We made it mobile friendly, mobile responsive. You don’t need passwords to log in. You can do OTP notification. One of the things we learned is how betting companies have penetrated through Africa. They have used the cell phone very effectively.

It keeps the prices low when you have a digital platform, but it also makes it convenient for people to actually access your platform. Then you have to use mobile money. Mode of payment is very simple. In Kenya, M-Pesa penetration is 96%. So you basically have mobile money as a way of paying for your service. And then I guess the one thing that to keep it profitable now is to work with multiple partners on revenue sharing modes.

And then work on models that are simple. Like if it’s a subscription, it has to be very basic. Netflix has penetrated through Africa because Netflix will charge what? Something close to $10, maybe $9 per month. So Africa has not developed the biggest subscription culture. So if you’re going to have any product that’s on a subscription model, you need to keep those costs low.

Then possibly allow those who want to have priority listing, let’s say on the directory or pay for their own space to come fast and stuff like that, allow them to pay more, but keep the prices down. Because one of the things that’s happening, and I’ll tell you the truth, it’s not that Africans don’t have digital tools. In Kenya right now, we are looking at over 45% internet penetration. And we are looking at so many people having smartphones, almost 50% mark. But you have many people with digital tools who have not embraced a digital culture. They’ll use it to do WhatsApp, they’ll use it to do Facebook, they’ll use it to send money and receive money and buy stuff, but they won’t use it to shop.

So the e-commerce platform grows more. The digital tools exist. I think it was a Nigerian writer who actually got to me when he said the biggest success for African startups would be to online, offline people who have online tools. Does that make sense to you?

The reason why I’m going back to what I said when you said, how do you hope to stay ahead? What is a strong brand? A strong brand has confidence, has trust, has testimonials that back it, has a mechanism. It is like on our platform, the Red Book, you cannot list without being vetted. If you’re selling a casket. We will allow you to apply to be listed. We will allow you to actually open an account, but we will not publish the account until we verify that you actually exist. That is what we hope to build as a strong brand so that it is verifiable.

So it would be very important to ensure that to grow an online populace. Because people have online tools. They have online gadgets. But they have not fully adopted the online culture, except in some cases. When it comes to Western Union, they will use it. Moneygram, they will use it. PayPal, they will use it. eBay, they will buy stuff from there.

But you know why? Those are strong brands that tell you every time you buy from us, what you’re buying is verifiable. The supplier you’re dealing with is verifiable, and we’ve got rules to deal with this. We want to make this the same. On our funeral platform right now, if you do a death notice, we have to verify that the death is actually linked to a funeral home. So that we don’t have a fake death notice.

Building a brand requires the brand’s reputation to be built in the way it conducts its business, in the way it treats customer complaints and in the way it manages its customer service. That’s why I said the biggest thing we’ve learned from our background is we must build a strong death care brand.

Can You Share with Me an Example of a Customer Success Story or a Particular Meaningful Experience that Highlighted the Positive Impact of Safiri Salama on a Family or on a Community?

Yes, I can. The first success story is myself. And this is because remember when I started, I actually told you one of the challenges for my son was, why isn’t granddad online? So what our platform does both on death notices and on memorials, is that when you open a memorial on our platform, it gives you a distinct URL address that Google can find.

My father’s name prior to 2019 did not exist online. But after Safiri Salama, he was the first customer that we input. So that now if you are to check. My father’s name is Benjamin Nyongesa Wanyoni. If you are to search for him, Safiri Salama picks him up.

So, I’m the first beneficiary of this whole story because I was able to immortalize my own father. I had a friend who when I discussed this idea with, and in the first one, two years, we were actually giving out free death notices, free memorials. We still have a mix of that even this year, just to make sure more people experience this. So I had asked him whether I can give him a free memorial for his father. He’s actually a famous broadcasting colleague. And he was very touched because we were having lunch. So I showed him the website and he walked me down to his car after we finished lunch and he said, I need you to see something.

And on the dashboard of his car was his father’s picture. And he said, John, my father died before I was 10, I’m 55 right now. I keep sometimes forgetting what he looks like. So I keep his picture on my dashboard every day to remind myself. And I said, you don’t have to just work with the picture. You could have him on a memorial website that can be accessed by all your relatives across the world. Because he said, my relatives are in three continents. And there’s so many children named after my father who don’t actually know him. Because most of the hard copy pictures are kept by my mother. And we only get to look at the album again during my dad’s memorial.

But remember, this was 40 something plus years ago. So by creating a memorial website on our platform, he said, what you have done, there are tens and tens of young descendants of my father and his brother’s kids, and our entire family, who are now able to actually access this man and access his memory wherever they are, via a phone, via a laptop.

I met a Google representative who I was discussing this issue with. And they said, John, I don’t think you’re building a death care platform. You’re actually building an African library. Because to the best of my knowledge, Africans don’t write their stories when they’re still alive. You mostly write them when you’re dead. And which is actually funny, but true, that most of our histories are contained in something we call the funeral program. That’s when it’s written, he was, he came, he married, he went to this school. But where do those copies actually go? We lose them, and we lose the pictures as well. So this person told me, John, you’re actually building an African library.

And I think this was like two years ago. It gave me a very good outlook of what it is we are trying to do here. I don’t know whether this would be appropriate, but since we are in a beta version, we have a mixture of both paid and free death notices and free memorials and paid for memorials. We wouldn’t mind actually giving you a taste of what it looks like by gifting you a two year subscription for your mother. For you, because the truth of the matter is my daughter who was born in 2012 acts like she knows my father who died in 2003, but it’s simply because of the platform.

She can access him, she knows what he looks like. She teases my beard, you know you look like grandpa, but where did she get that information from? So it would be nice to consider doing that for your beloved mother as well. And we as Safiri Salama would like to actually give you that. We think in the next one or two years, we will consider coming into the Nigerian market. We want to do a Kenyan market fit to understand how to work, how to monetize it, and how to keep its costs low. And then also understand the culture of different people. So that’s what I will say.

There’s a Sudanese, we gave this to. There’s a South African, we gave this to. And there’s a Zambian, we gave this to. There’s a Ugandan, we gave this to. Because actually it can operate multi-country. Even though right now, it is Kenya-specific. But it allows you to input information from different countries on it. We think it’s an experience that we can share as Africans in the sense that it is not about remembering the dead, it is about celebrating the memories of those who came before us. Of those who came before us because how do you know who you are unless you know where you came from?

Click here to read the part three of this interview.