If you’ve ever backed an African startup (or are thinking of doing so) you’ll know the excitement: the tech‑enabled business, the growth potential, the massive under‑served markets.

But then there’s the question that often gets whispered: How and when do we get out? In other words, what’s the exit strategy?

In Africa’s startup ecosystem this question is relevant. The continent offers huge upside but also structural quirks, regulatory complexity, fragmented markets, less‑mature exit routes.

For investors, knowing how exits work (or don’t) is key. For founders, building with an eventual exit in mind can make all the difference.

In this article, I’ll walk through what exit strategies look like for African startups, what investors should keep an eye on, and how real‑life examples illustrate the path.

What is an “exit strategy” and why it matters

When we say “exit strategy” in a startup context we mean how investors (and sometimes founders) plan to recover their investment or earn returns via a sale (merger/acquisition), IPO, buy‑back, secondary sale, etc.

On the African continent this matters for a few reasons:

- Exits provide liquidityc, the payoff for risk. Without them, investors hold indefinitely.

- They signal maturity of the ecosystem: when companies are being bought, that shows value is recognised. (One article described exits as “a sign the ecosystem has reached a certain level of maturity.”)

- For founders, knowing there is a plausible exit path helps with planning: structuring the business, governance, growth, etc.

- For investors in Africa, exit opportunities have often been cited as a top concern.

So yes, exit strategy isn’t just something for later. It influences how you build the business, how you invest, and how you position the startup.

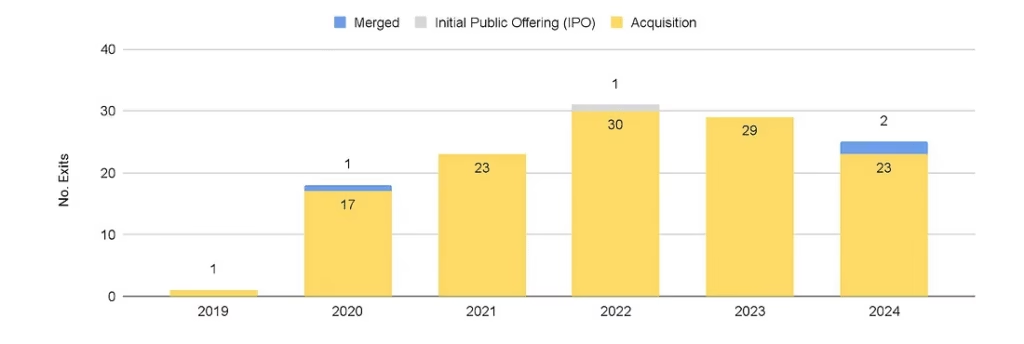

Startup exits in Africa: what the data tells us

Let’s take a look at what’s happening in Africa when it comes to startup exits, and be honest: there are both encouraging signs and persistent issues.

Exits are still relatively few and modest

One key report shows that between 2015 and 2023 the expected value of exits in African tech might have been $20 billion; reality: only about $2‑3 billion were realised.

Another article notes that 76 % of LPs (limited partners) point to “limited exit opportunities” as the biggest challenge in African PE investing. And most exits happen via acquisitions rather than IPOs. The public markets simply aren’t as mature across Africa.

Some sectors lead; time horizons are long

In Africa, fintech has been a dominant exit sector. For instance, some data show fintech accounting for 31 % of acquisitions in one recent year. An interesting insight: the most successful exits often take 10 years from founding to acquisition. Not a quick flip.

Exits vary by geography; structural factors matter

Some countries, even though they raise lots of venture capital, lag in exit volume. For example, Nigeria and Kenya raise major funding but rank behind Zambia, Tanzania or South Africa when it comes to exit value. Structural issues such as smaller public markets, regulatory differences, fragmented markets across Africa, all make exits more complex.

So, yes, exits are happening. But the path is slower, harder, and different compared to more mature ecosystems. Which means investors and founders need to plan with these realities in mind.

Read Also: Ariaria International Market Aba: Africa’s Hub of Creativity and Trade

Exit strategies for African startups (and what investors should ask)

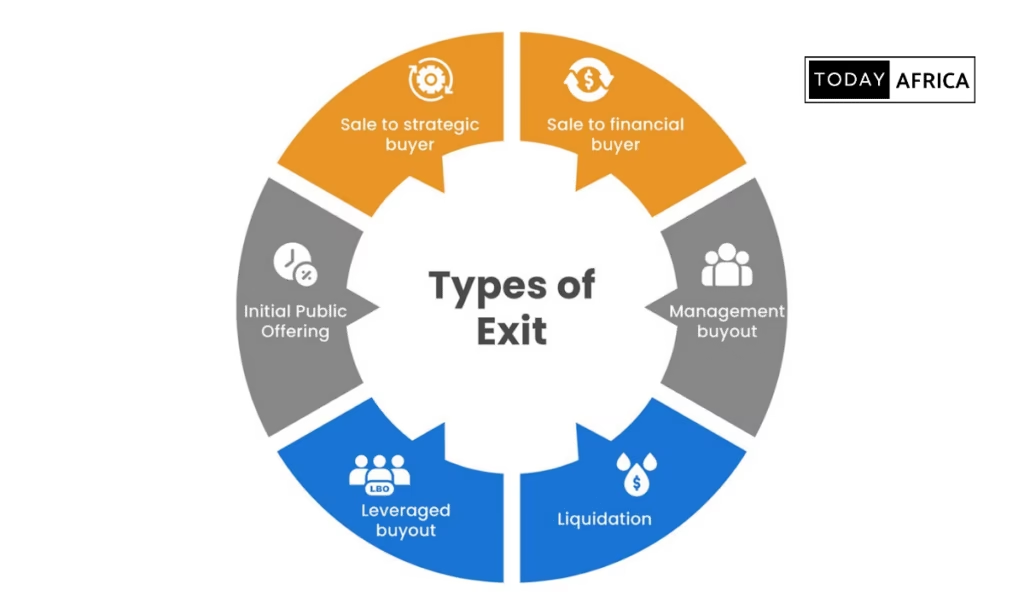

Here are the major exit‑routes you’ll see in Africa, and what I think investors should be asking, be it from the perspective of fund‑making or deal‑making.

1. Merger‑or‑acquisition (M&A)

The startup is bought by a larger company and could be local, regional, or international. Given that IPO routes are fewer, M&A tends to be the most plausible liquidity path.

What investors should check:

- Who could be a buyer? Domestic competitor, regional player, global company expanding into Africa.

- Does the business have appeal to a buyer, in terms of technology, market share, talent? One article said African tech talent is increasingly seen as a strategic asset.

- Are operations professionalised? Buyers look for governance, financial systems, scalable operations. One piece about PE investors in Africa emphasised majority‑ownership to enable control and process improvement.

Example: Paystack (Nigeria): Founded in 2015; acquired by Stripe in 2020 for over $200 million.

2. Buy‑back/secondary sale

The founder or management buys out investors; or shares are sold to secondary investors rather than via the classic IPO or M&A. In a market where exit options are limited, this can be a way for early investors to get liquidity.

What to ask

- Is there a plan or possibility for management buy‑out?

- Are shareholder agreements structured to allow secondary sales?

- Are liquidity events contemplated early?

Note: In many African deals this is less common compared to M&A, but worth thinking about.

3. Initial public offering (IPO) or listing

Listing the startup on a public exchange either domestic or international. However, there are several reasons why is less common in Africa, which include smaller local exchanges, regulatory hurdles, and investor preference for simpler routes.

What to ask: Is the company being built with the governance, financial transparency, scale and growth to support a listing? Are there viable markets domestically or abroad where listing is plausible?

Data point: One source noted that among 33 African PE exits in a year, not one was via IPO.

4. Strategic sale to a local/regional player

The startup is sold to a company in Africa (or adjacent markets) that sees value in scaling the business across the continent. African markets are fragmented; consolidation via an exit to a regional player can open cross‑border expansion and valuations.

What to ask

- Does the business model allow cross‑border scaling?

- Does the founder or investor team understand how to structure for acquisition by a strategic buyer?

Example: Tunisian startup Expensya was acquired by Sweden’s Medius in a cross‑continental model, showing how an Africa‑based company positioned itself globally.

Read Also: African Second-hand Economy: The Billion-dollar Industry

What investors should know (and discuss with founders)

Because Africa has some specific realities, here are extra questions and themes to discuss.

Market‑fragmentation and cross‑border complexity

Unlike in some other markets where scaling nationally gives you a large market, many African startups must think pan‑African (or beyond) early. Regulation, logistics, consumer behaviour vary significantly from one country to another.

This affects exit timing and strategy: a buyer might value a business that already operates in 3‑5 markets rather than just one. In a study of African investments, cross‑border collaboration and human capital were among the key factors influencing deal size and exits.

Governance, control and structure from day one

An article by AVCA argued: “Take control … majority or outright ownership … installing experienced managers … proper systems” helps to make companies attractive for exit.

- For investors: ask about share classes, governance, board composition, exit rights.

- For founders: think about how you structure the company so that future buyers won’t balk at weak governance or opaque operations.

Patience and realistic timelines

Many African exits take longer. One article suggests that the “most successful exits take around 10 years” in Africa. So, if you’re an investor, don’t bake in a 3‑5 year timeline unless you have a very special case. If you’re a founder, be thinking long game.

Valuation expectations vs exit realities

There’s a gap between how much capital has gone into African tech (billions) and how much has been realised in exits. You may be investing in potential rather than guaranteed exit value. So risk‑adjusted returns matter more. For founders, focusing on unit economics, profitability, real value matters more than hype.

Sector moments and global trends

Some sectors are catching up: climate tech, logistics, B2B commerce. One article noted climate tech startups raised $1 billion in African tech funding in 2023 and may be ripe for acquisitions. Investors should watch which sectors are being eyed by global incumbents and are likely to spark exit activity.

Local buyer universe and partial exits

Because sometimes the local buyer universe is limited, investors and founders may consider partial exits or staggered exits (e.g., anchor investor buys minority, etc). Also, thinking about regional strategic acquirers (not just US/EU) is wise.

Read Also: African Startups Tackling Energy and Waste: A Look into the Cleantech

What real African exits teach us

It’s always more useful when we ground it in what’s happened in Africa. Let’s look at a couple of narratives.

Paystack (Nigeria)

Founded in 2015 by Shola Akinlade and Ezra Olubi, Paystack provided payments infrastructure for African businesses. In October 2020, Stripe acquired Paystack for over $200 million.

What we learn:

- They built strong product‑market fit (serving 60,000+ businesses) and were accepted into Y Combinator (which helped global exposure).

- They weren’t actively looking for sale when Stripe approached, so sometimes exit comes when you’re focused on building.

- The deal signalled to the ecosystem: “Yes, African startups can exit at scale.” That helps others.

- For investors: control, operational maturity, a credible path to growth mattered.

Expensya (Tunisia/France)

Started in 2014, Tunisian engineers built a business‑expense management platform, set up operations into Europe (France) and global markets. They were acquired by Sweden’s Medius for over $100 million.

What we learn:

- Starting in Africa but thinking globally helped.

- Having an international business model improved exit potential.

- It shows that exit isn’t only for Nigeria/Kenya but across the continent.

- For investors: note that dual‑entity structure (Africa + Europe) can reduce risk and open buyer universe.

Broad ecosystem insight

A recent article shows that in Africa the ratio of deals to exits is about 20:1, meaning for every 20 deals there is roughly 1 exit. That’s steep compared to some other regions.

- For investors, that implies high selectivity.

- For founders, know the competition and realise that many will not exit, so build real value.

Read Also: Fintech 3.0 in Africa: What Comes After Payments?

What investors should ask (checklist)

When evaluating a startup in Africa, to increase exit potential, here are some questions worth asking:

- Is there a clear “what’s next” path for this business after investment? (scale, region, market)

- Is the startup building something attractive to a strategic buyer (e.g., tech, user base, data, cross‑border capability)?

- Has the governance structure been considered: share classes, board, audits, minority protections?

- Does the company operate across multiple markets (or have potential to), and can it be scaled?

- Have timelines been set realistically? Are we prepared for a longer horizon?

- What size exit are we realistically targeting? Are valuations aligned with African multiples (which may be lower than US/Europe)?

- Who are potential acquirers? Local, regional, global? Have relationships been cultivated?

- How is the regulatory environment in the markets the startup operates in? Could it affect exit readiness?

- Is there a margin for partial exits or secondary sales if full exit isn’t immediately possible?

- For the founder‑investor team: Are we aligned on exit expectations, investor rights, founder roles post‑exit?

How founders should think about exits

It’s not only investors’ job. If you’re a founder of an African startup, thinking about exit early can shape your strategy, correctly.

- Build for scale: you might start in one country, but if you’re only ever going to serve one small market, buyer interest may be limited.

- Professionalise early: investors and acquirers alike like metrics, audits, structured management, governance.

- Structure your equity and share‑classes early with exit possibilities in mind, minority shareholders who have no exit route will push for liquidity.

- Understand that in Africa the exit won’t always look like Silicon Valley. It might be acquisition by a regional player, or a strategic buyer, or a slower timeline. That’s okay, adapt.

- Keep buyer market in mind: who might buy you? Can you build something attractive to them?

- Don’t get obsessed with exit so much that you lose focus on growth, customer value, business model. But keep exit in mind.

- Align with your investors on timeline, expectations, and eventual roles post‑exit. Misalignment causes problems.

Read Also: State of Artificial Intelligence in Africa: Opportunities & Challenges

Exit strategy pitfalls specific to Africa

Because no article would be complete without a few warnings.

- Over‑reliance on IPO: Expecting going public may be unrealistic in many African contexts. The buyer universe is smaller; the listings fewer.

- Expecting quick exit: As noted, many African exits take a decade or so. If you’re pushing for quick flip you might miss value or get stuck.

- Ignoring regional regulatory risk: A business operating across borders might face regulatory shifts, currency risk, or governance gaps that slow exit.

- Undervaluing a local buyer: Sometimes global buyers are few. Local or regional acquirers might be more realistic, but entrepreneurs often aim for “global buyer” prestige, which may narrow opportunities.

- Neglecting alignment on exit: Founders and investors may drift apart in expectations, one wants long‑term build, the other wants exit sooner.

- Underestimating integration risk: For M&A exits, integration into the acquirer is often a challenge. If your business is too niche or too standalone, a buyer might shy away.

Emerging trends & what to watch in Africa

Here are a few signals I think investors should keep on their radar for exit potential in African startups.

Rise of climate‑tech and “impact” sectors

An article noted climate‑tech startups in Africa raised about $1 billion in 2023 and could become ripe for acquisitions. As global companies look to expand ESG footprints, African startups that bring climate solutions, energy tech, or resource efficiency could attract strategic buyers.

Increasing cross‑border acquisition interest

Because major African markets are fragmented, startups that successfully scale across borders become more attractive. Investors should favour founders with pan‑Africa (or global) vision.

More interest in secondary or partial exits

Given the structural challenges, we may see more deals where founders or early investors take partial exits, or companies are sold in parts, or where secondary markets in Africa start to mature.

Talent and IP as exit assets

One write‑up noted that African startups are getting noticed not just for market size but for talent and IP, especially in technical fields, which may attract acquirers.

Professionalisation and governance as differentiators

Startups that demonstrate audited financials, strong boards, clean shareholding, and governance are more likely to exit successfully. This is increasingly recognised in Africa.

Realistic exit timeline: what to expect

Here’s a rough guideline (not a guarantee) of what an African startup’s exit journey might look like — and where investors should keep expectations.

- Years 0–2: Product‑market fit, local traction

- Years 2–5: Scaling within home market, perhaps initial cross‑border moves

- Years 5–8: Operational maturity, governance, potential buyer interest if metrics strong

- Years 8–12+: Likely window for major exit (M&A) if everything aligns

So if you’re investing with a 3‑5 year horizon expecting a big IPO or sale, you may need to recalibrate. If you’re a founder hoping to sell in 4 years, be realistic. But if you’re playing the 7‑10 year game with scale, cross‑border, governance, you’ll be in better shape.

Conclusion

Exit strategies for African startups are not just “nice‑to‑have”, they’re fundamental.

Without them, the incentive for investment weakens, founders are stuck, ecosystems stagnate. When exits happen they validate the model, they fuel new funds, they send a signal.

The good news is that we’re seeing exits in Africa.

The not‑so‑good news: they are modest, slow, and often under‑recognised. But I think maybe the most important thing is that the playbook for Africa isn’t simply copying the US/Europe.

It’s shaping something that fits the region’s realities.

I’d love to know:

- what exits in Africa do you feel we under‑celebrate or ignore?

- what sectors do you think will spark the next wave of exits?

If you found this helpful, perhaps share it with a fellow investor or founder who’s navigating the African startup journey.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, or legal advice. Readers should conduct their own research and consult qualified professionals before making any investment or business decisions. The author and Today Africa are not responsible for any outcomes resulting from the use of this information.

Leave a comment and follow us on social media for more tips:

- Facebook: Today Africa

- Instagram: Today Africa

- Twitter: Today Africa

- LinkedIn: Today Africa

- YouTube: Today Africa Studio