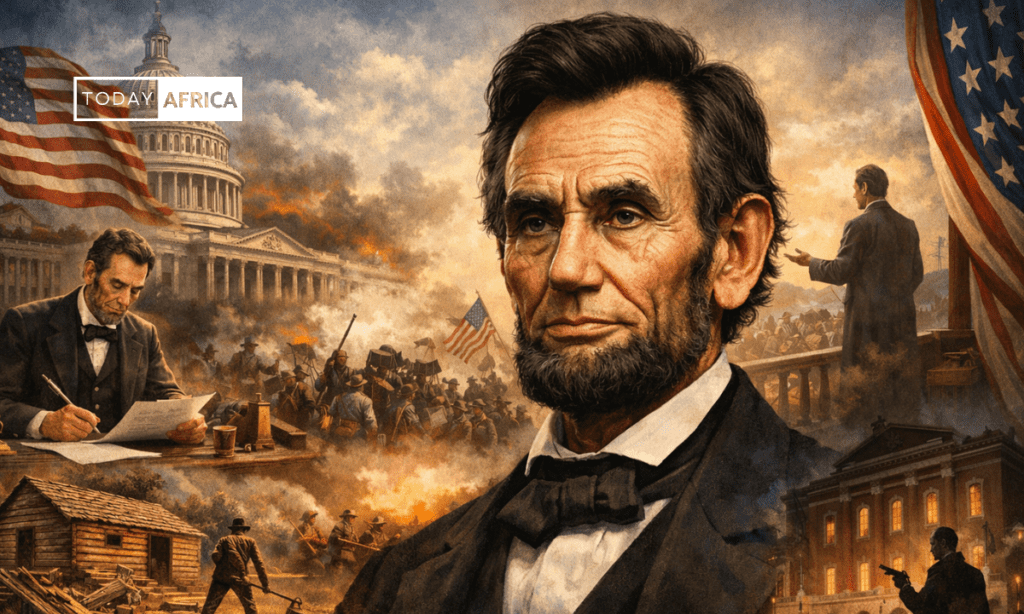

Abraham Lincoln remains one of the most studied political leaders in modern history, not merely because he presided over the United States during its most violent internal conflict, but because his presidency fundamentally reshaped the legal, economic, and moral architecture of America.

His leadership during the Civil War (1861–1865) preserved the Union, ended the institution of slavery, and redefined the scope of federal authority.

Any serious biography on Abraham Lincoln must move beyond mythology and examine the structural forces he navigated: sectional economic divides, constitutional constraints, wartime executive power, and the unfinished project of Reconstruction.

Born into poverty and largely self-educated, Lincoln rose through law and state politics into the presidency at a moment when the American political system was fracturing.

His life illustrates the intersection of frontier society, legal institutions, party realignment, and constitutional crisis in 19th-century America.

Early life and education (1809–1830)

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in Hardin County, Kentucky (now LaRue County), to Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln.

His upbringing on the frontier exposed him to subsistence farming, manual labor, and the economic precarity of rural households in early America.

Formal schooling was limited, estimated at less than one year in total, but Lincoln pursued extensive self-directed study, reading works such as the King James Bible, Aesop’s Fables, Shakespeare, and later, legal treatises.

In 1816, the Lincoln family moved to Indiana, partly due to land title disputes, an early exposure to property law issues that would later shape Lincoln’s respect for legal systems and contracts.

His mother died in 1818, and his father remarried in 1819. In 1830, the family relocated to Illinois, a state that would become central to his political rise.

Lincoln’s early adulthood included work as a rail-splitter, store clerk, surveyor, and postmaster. These roles provided him with practical familiarity with frontier commerce and local governance.

His entry into politics began in the Illinois State Legislature in 1834, where he served four terms as a member of the Whig Party.

Legal career and political formation (1834–1854)

Lincoln was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1836 and built a successful legal practice in Springfield.

He became known for his methodical preparation, clarity of argument, and ability to translate complex legal issues into accessible language for juries.

His law practice included cases involving railroads, property disputes, debt, and commercial contracts, exposing him to the economic transformations driven by transportation and westward expansion.

During this period, Lincoln aligned with the Whig Party, which supported internal improvements, banking institutions, and infrastructure development. His political thinking reflected the Whig emphasis on economic modernization and federal support for development projects.

Abraham Lincoln served a single term in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1847 to 1849.

His tenure coincided with the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), which he criticized as an unjust expansionist conflict initiated under questionable executive authority by President James K. Polk.

This skepticism toward executive overreach would later contrast with the expansive wartime powers Lincoln himself would exercise as president.

The most transformative political development of this period was the intensifying debate over slavery’s expansion into new territories.

The Compromise of 1850 and later the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed territories to determine the legality of slavery through popular sovereignty, destabilized existing political alignments.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act, in particular, led to violent conflict in Kansas and catalyzed the formation of the Republican Party.

Lincoln re-entered national politics as a founding member of the Republican Party, which opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, though it did not initially advocate immediate abolition in states where slavery already existed.

The Lincoln–Douglas debates and national prominence (1858)

In 1858, Lincoln challenged incumbent Senator Stephen A. Douglas in Illinois. Although Lincoln lost the Senate race, since senators were then elected by state legislatures, the Lincoln–Douglas debates elevated his national profile.

In these debates, Abraham Lincoln articulated a foundational principle: that the United States could not endure permanently “half slave and half free.”

While he did not initially call for the immediate abolition of slavery nationwide, he argued that its expansion would nationalize and entrench the institution.

The debates also highlighted constitutional tensions. Douglas advocated popular sovereignty, allowing territories to decide the status of slavery.

Lincoln countered that slavery’s moral and political implications transcended local control.

These debates established Lincoln as a national Republican leader capable of articulating a coherent anti-expansion position grounded in constitutional argument rather than rhetoric alone.

Read Also: The biography of Malcolm X: Power, race, & black consciousness

Election of 1860 and secession crisis

Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th President of the United States in November 1860, winning approximately 40% of the popular vote in a four-way race.

He carried every free state but no slave state, a stark indicator of sectional polarization.

Following his election, seven Southern states seceded before his inauguration in March 1861, citing concerns that the Republican administration would threaten the institution of slavery.

After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, four additional states joined the Confederacy.

The Civil War began not merely as a military conflict but as a constitutional crisis. Lincoln termed the war primarily as a struggle to preserve the Union, arguing that secession was legally void.

His interpretation relied on the premise that the United States was a perpetual union rather than a voluntary compact among sovereign states.

Wartime leadership and executive authority (1861–1865)

Lincoln’s presidency fundamentally expanded the scope of executive power.

During the war, he suspended habeas corpus in certain regions, authorized military trials, and implemented a naval blockade of Southern ports, all measures justified under his constitutional authority as commander-in-chief.

Historians and legal scholars continue to debate the implications of these actions. The suspension of habeas corpus, for example, raised concerns about civil liberties.

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney challenged Abraham Lincoln’s authority in Ex parte Merryman (1861), but Lincoln proceeded, arguing that extraordinary measures were necessary to preserve the nation.

Economically, the war accelerated federal involvement in finance. The Legal Tender Act of 1862 authorized the issuance of paper currency (“greenbacks”), and the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 created a more centralized banking system.

The Morrill Tariff and the Homestead Act of 1862 further shaped national economic development by promoting western settlement and industrial protectionism.

These measures restructured the relationship between federal authority and economic policy, setting precedents for modern centralized governance.

Read Also: 25 recommended biography books for the voracious reader in you

The emancipation proclamation and the abolition of slavery

Abraham Lincoln’s most consequential act was the Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863. The proclamation declared enslaved persons in Confederate-held territory to be free.

While it did not immediately abolish slavery nationwide, since it did not apply to border states loyal to the Union, it redefined the war as a struggle against slavery.

The proclamation had significant strategic implications. It discouraged European powers, particularly Britain and France, from recognizing the Confederacy, as public opinion in those countries had turned against slavery.

It also authorized the enlistment of Black soldiers into the Union Army. By the end of the war, approximately 180,000 Black men had served in the Union forces, according to National Archives data.

Lincoln later supported the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which formally abolished slavery in the United States. The amendment was passed by Congress in January 1865 and ratified in December of that year, after Lincoln’s death.

Reelection and the question of reconstruction

Abraham Lincoln was reelected in 1864 amid ongoing war, under the National Union Party banner, a temporary coalition of Republicans and War Democrats.

His second inaugural address, delivered in March 1865, emphasized reconciliation over retribution, stating that the nation should proceed “with malice toward none, with charity for all.”

Lincoln’s vision for Reconstruction favored relatively lenient reintegration of Southern states, provided they abolished slavery and pledged loyalty to the Union.

His approach was pragmatic and focused on restoring political stability, though critics argued it lacked clear guarantees for the rights and protection of formerly enslaved individuals.

The war effectively ended in April 1865 with General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House.

Read Also: A Look at the Charlie Kirk Biography: Major Conservative Voice

Assassination and aftermath

On April 14, 1865, just days after Lee’s surrender, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. He died the following morning, becoming the first U.S. president to be assassinated.

His death altered the trajectory of Reconstruction. Vice President Andrew Johnson assumed the presidency and pursued policies that clashed with Congressional Republicans, leading to a more contentious and fragmented Reconstruction era.

Legacy and institutional impact

Lincoln’s historical legacy is anchored in three primary domains: preservation of the Union, abolition of slavery, and expansion of federal authority.

- Preservation of the union: The Civil War resulted in approximately 620,000 to 750,000 military deaths, according to demographic analyses by historians such as J. David Hacker. The war settled the constitutional question of secession and affirmed federal supremacy.

- Abolition of slavery: The Thirteenth Amendment eliminated the legal foundation of slavery, though it did not resolve systemic racial inequality. The subsequent Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments further redefined citizenship and voting rights.

- Executive power and modern governance: Lincoln’s use of emergency powers during wartime expanded the practical scope of presidential authority. Later presidents would invoke similar precedents during crises, from World War I to the Great Depression and beyond.

Scholarly evaluations often rank Lincoln among the top U.S. presidents. In surveys conducted by institutions such as C-SPAN and the American Political Science Association, he consistently ranks in the top tier for crisis leadership, moral authority, and vision.

However, critical scholarship also notes the limits of his policies. His racial views evolved over time, and early in his presidency he entertained proposals for colonization (the relocation of formerly enslaved people outside the United States).

His positions shifted significantly as the war progressed, reflecting both moral development and political necessity.

Read Also: Captain Ibrahim Traoré: The Transitional Leader Transforming Burkina Faso

Conclusion

The biography on Abraham Lincoln is not merely a narrative of personal advancement but a case study in leadership during systemic crisis.

He navigated the collapse of party structures, the secession of states, constitutional ambiguities, and a war that tested the viability of republican government.

His presidency altered the trajectory of the United States, embedding principles of national unity and formal equality into its constitutional framework.

At the same time, the incomplete realization of those principles, particularly regarding racial justice, underscores the limits of leadership constrained by political realities.

Lincoln’s enduring relevance lies in the institutional precedents he established:

- the conditional expansion of executive authority in crisis

- the federal government’s role in shaping economic development

- and the constitutional commitment to freedom as a national principle rather than a regional compromise.

In assessing Lincoln, it is necessary to separate symbolism from structure. He was neither a mythic figure detached from politics nor a purely pragmatic operator devoid of moral vision.

He was a political leader whose decisions continue to inform debates about constitutional power, civil rights, and the responsibilities of executive leadership in moments of national fracture.

Leave a comment and follow us on social media for more tips:

- Facebook: Today Africa

- Instagram: Today Africa

- Twitter: Today Africa

- LinkedIn: Today Africa

- YouTube: Today Africa Studio

![Biography of Tony Elumelu [Investor, Entrepreneur, & Philanthropist]](https://todayafrica.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Blue-Simple-Dad-Appreciation-Facebook-Post-1200-×-720-px-7-1.png)