In Nigeria, where 1 out of every 13 babies never sees their first birthday, and countless mothers silently battle postpartum depression, one doctor is reimagining what healthcare could look like.

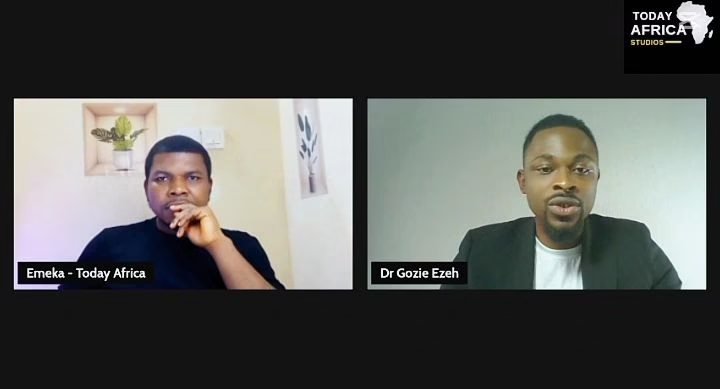

Meet Dr. Gozie Ezeh, a medical doctor by day and a fundraising strategist by night—whose life’s mission is to scale impact beyond the walls of hospitals.

Through SweetMom, he is building a doctor-led care, education, and community platform designed to support Nigerian mothers through their baby’s first year of life. And with Funds for Impact, he is helping businesses, startups, and nonprofits access the funding they never knew they could get.

In this conversation, Dr. Gozie Ezeh shares his journey of blending medicine, technology, and strategy to create solutions that matter—not just for individuals, but for communities across the continent.

Tell us more about yourself

By day, Dr. Gozie Ezeh wears the white coat of a Nigerian medical doctor. By night, he switches hats, stepping into the role of a fundraising strategist. He calls this dual life both demanding and purposeful.

“I’m the founder of SweetMom and Funds for Impact,” he explains. “With SweetMom, we’re building a platform for moms across Africa, especially first-time moms.

And with Funds for Impact, I support nonprofits, changemakers, and impactful startups to raise the funds they need to execute their work.”

It is a balancing act of two passions—medicine and impact—both of which are rooted in a vision of scaling care beyond the four walls of a clinic.

What inspired you to study medicine and specialize in maternal and infant health?

The dream began when he was just seven years old. In primary school, he played the role of a doctor in a stage play. It was a small moment, but it planted a lasting seed.

“As I got to know what a pediatrician means, I said I was going to be a pediatrician,” he recalls.

Medical school, however, reshaped his vision. While he valued one-on-one patient interactions, he wanted more. “I started thinking, how do you scale your impact? How do you reach more people? I prefer one-to-many interactions,” he says.

That search for scale led him toward maternal and infant health. “If we can support moms across Africa, it’s going to be very impactful. I’ll be doing more justice with my skillset as a doctor if I can serve a million moms than just serving one mom at a time.”

Is there any personal experience or story that led you to start SweetMom?

The defining moment came during his fifth year in medical school. While scrolling through Facebook, he saw a young mother post a desperate plea: her baby was feverish and convulsing. The replies in the comments horrified him.

“Someone said to put palm oil in the baby’s nose. Another said place the baby near the fire and the convulsion will stop,” he remembers. “I was disappointed and angry that some moms did not really know the basic things on how to care for their babies.”

That anger turned to grief when he saw another mother comment that she had lost her child. “What if she had access to the right knowledge, the right community, the right resources?”

The tragedy revealed a wider crisis. Nigeria records seven million births each year, but one in thirteen babies does not live to see their first birthday. “That means 500,000 babies die annually. In 30 minutes, we lose 30 babies. It’s the same story across Africa,” he says.

For him, sitting in clinics waiting for patients would never be enough. “There has to be different ways,” he insists. “That’s why SweetMom was born.”

See Also: Nonhlanhla Shembe on Why “Visibility is Currency” for Small Businesses

Tell us more about SweetMom, the services, and the products

Launched in March, SweetMom is still in its early days, co-founded with two other doctors and supported by a team of healthcare professionals. They began with focus groups, listening carefully to mothers.

“What we discovered was not just that babies are dying, mothers too are not thriving,” he explains. Maternal depression is widespread—estimates put the rate between 8% and 30%. “If we take the average, that’s about 22%. One in five moms are suffering.”

This reality shifted the vision. “If we help moms thrive, they can help their babies thrive,” he says.

SweetMom’s model begins with education—accurate, accessible health information—delivered inside a supportive community of mothers and guided by healthcare professionals.

From there, they plan to expand into services like telehealth and products designed for maternal well-being.

What are some of the most common challenges first-time moms face?

“The first one is loneliness,” he says. Postpartum blues often evolve into depression, but too many women endure it in silence. Cultural expectations tell them to “muscle it up” and suppress their struggles.

The second challenge is misinformation. He remembers a 19-year-old mother who told him she gave her baby paracetamol whenever the weather was hot.

“Would you take paracetamol because of hot weather?” he asked her. “She was simply afraid and didn’t know what else to do.”

Healthcare education is scarce. Antenatal classes are too few and too brief, and after delivery there is often only a six-week checkup. “What happens between then? What happens beyond? There’s no real system to teach women what to do.”

For him, bridging this information gap is one of the simplest yet most powerful interventions.

What then is the role of the fathers in all these?

“The fathers’ role should be support,” he says firmly.

He has seen the difference it makes when husbands share night duties, soothe babies, and give mothers the chance to rest. “Moms told me that because they had supportive husbands, they didn’t feel the pain of early motherhood so much.”

He points to Denmark as an example, where fathers take over childcare after birth so mothers can fully recover. “It doesn’t hurt for fathers to also know basic things about childcare and emergencies. Support is key.”

Read Also: Hortense Mbea: Building Afropian to Celebrate African Heritage Through Fashion

How does SweetMom provide support differently from traditional medical consultations?

Traditional healthcare is reactive: mothers go to the hospital when something is wrong. SweetMom aims to be proactive, focusing on prevention and education.

“We are going to meet people where they are, not wait for them to come,” he says.

That means using media—TikTok, social platforms, and other low-cost channels—to deliver knowledge. It also means building communities that normalize conversations about depression and maternal struggles, rather than leaving women to suffer silently.

The stakes are high. Nigeria’s doctor-to-patient ratio is dismal—officially one doctor to every 4,000 or even 10,000 people. “Doctors are overworked,” he admits. “But I know this work is important, so I have to do it.”

What misconceptions about pregnancy and infant care do you encounter most often?

“Many mothers are not prepared for motherhood,” he says bluntly.

They underestimate the toll it takes. He recalls recent first-time mothers—one who endured a prolonged labor, another who underwent a C-section. “She said she’s not going to get pregnant again,” he recalls.

Preparation, he believes, helps adjust expectations and prevents burnout.

How do you strike a balance between medical science and cultural beliefs in maternity care?

Cultural traditions like omugwo—when a mother or mother-in-law comes to care for a new mom—offer vital support, but they also carry risks. Advice handed down through generations can be outdated or harmful.

Balance, he says, is not in rejecting tradition, but in grounding it with science.

“They should know the right thing according to science, then use that as a blueprint to evaluate whatever information comes from relatives or friends.”

See Also: How Amina Asu-Beks is Changing the Way Nigerians Shop

Tell us more about your other venture, Funds for Impact

Impact, for him, is non-negotiable. His passion for it deepened after working with a humanitarian NGO that supported war-displaced children. “I literally saw how giving somebody another chance at life can impact their life,” he recalls.

But he also saw the limits: NGOs faced constant financial strain. That challenge led him to grants, and soon others came asking for his help.

Today, Funds for Impact exists to solve Africa’s capital problem. “Every day I speak with innovative people solving real issues,” he says. “But they don’t have access to funding.”

The mission is simple: connect those solving problems with the resources they need to do it.

What gap did you see that led you to start Funds for Impact?

Too many organizations are not structured in ways that make them fundable. Some lack registration, governance, or sustainable program design. Startups often fail to test their ideas before seeking funding.

Funders, he explains, look for alignment with their priorities and proof of accountability. “They want to know they can trust this person to deliver. Some people get money and squander it.”

Funds for Impact helps nonprofits and startups restructure, pilot, and present themselves in ways that inspire confidence.

Do you think African nonprofits are adequately positioned to attract funding?

Dr. Gozie Ezeh doesn’t hesitate before answering: yes and no.

“Yes, in terms of good ideas,” he explains. “We have things that, if well executed, will make a lot of impact.”

But vision is not enough. Too many African nonprofits struggle with structure.

“Some of them don’t have governance, no board of directors, no advisors,” he notes. “How do you trust somebody with money if you’re not really seeing anything?”

For him, fundability is built on trust. An organization must show it has the systems, accountability, and governance that reassure funders their money will make real impact.

“There are certain things that make an organization fundable to show that they are trustworthy,” he says.

Read Also: Why Sarah Olagoke Believes Women’s Health is the Key to Community Growth

What are the mistakes these nonprofits are making, and how do you help them avoid them?

Most nonprofits that come to him fall into two groups: those just starting out, and those that have been running for a while but haven’t gained traction.

“Depending on their stage, I see the gap and help them restructure in a way that makes them more fundable,” he explains. For the early-stage organizations, he often recommends pilot programs.

“Do a test pilot to show that your idea, your program, or your project can actually succeed. That proof helps attract funding.”

For the more established groups, the problem often lies in presentation. Strong governance, ideas, and programs mean little if they aren’t communicated effectively. “

There’s a skill set to writing applications,” he says. “You have to show that the problem you’re solving is urgent—that it can’t wait. The problem must be poignant, painful, and immediate.”

Beyond urgency, nonprofits must demonstrate sustainability, accurate budgeting, and a clear theory of change. “If these things aren’t well captured,” he warns, “you might not get funded.”

What are the trends shaping your industries in Africa?

In healthcare, Dr. Ezeh sees technology as a lifeline. “Some telehealth companies are doing great in Nigeria and across Africa.

We need to leverage technology to deliver healthcare because the traditional means are not sustainable,” he says. Telemedicine is only the beginning. “AI is very big now. If we can leverage it properly, we’ll be able to make a lot of impact.”

Nonprofits, meanwhile, face a different challenge: shrinking donor pools. “Funds have dried up from different sources,” he explains. To survive, they must innovate.

He points to one nonprofit he works with that is venturing into agriculture to sustain its mission. “Their farming will fund whatever they’re doing and make it more sustainable.”

Startups, on the other hand, must be smart about capital. “At the early stage, investors aren’t really interested because you don’t have traction,” he says.

His advice: pursue non-dilutive funding, such as grants, first. “There are a lot of grants for African startups across sectors. Once you build traction, then investors and even private equity become possible.”

Read Also: How Victor Ogunbiyi is Using AI to Help Kids with Dyslexia, ADHD & Autism

What lessons from practicing medicine have influenced your leadership style as a founder?

Medicine, he says, has given him two leadership instincts: calmness and simplicity.

“Even if all hell is breaking loose, you maintain calm and know there’s a way out,” he says. Doctors learn to start with basics—vital signs—and build upward from there.

“That’s how I approach problems as a founder too. Break them down, simplify them, take tiny baby steps.”

He smiles at the memory of his own beginnings. “Where we are today is not where I started from. Back then, I was asking myself, how do I do this, how do I do that?

I tend to think far out into the future, but thinking far into the future doesn’t do anything unless you take the first step now.”

If you could design the Nigerian maternal healthcare system, what would it look like?

This is a question Dr. Ezeh has pondered for years, since medical school. He envisions a healthcare system designed not around institutions but around people—specifically, around mothers.

“What if the healthcare system is built around the mother?” he asks. “In most homes, it’s the mother that holds everything together. If anybody is sick, she’s the one who takes care of them first. Moms are like the first doctors in the house.”

He expands the thought outward: families are the fabric of society, and mothers are at their center. “If you take care of the mother, you take care of the family. If you take care of the family, you take care of society,” he says.

His vision is simple but profound: equip mothers to be efficient agents of healthcare change. The ripple effects, he argues, would transform communities.

Read Also: Why Thuli Zikalala Left a 9–5 Job to Serve South Africa’s Deaf Community

Where do you see SweetMom and Funds for Impact in the next five years?

For SweetMom, the goal is ambitious yet clear: reach one million mothers across Africa.

“We have the youngest population in the world. That means in the next couple of years, more than half of our population will be moms,” he explains.

“We cannot afford to take the lives of the next generation casually. SweetMom must be at the forefront of caring for African babies.”

The horizon stretches further. In twenty years, he hopes to look back and see a healthier African population, with the SweetMom model spreading beyond the continent to other regions in need.

Funds for Impact, on the other hand, is harder to quantify. “The truth is, I cannot even tell you exactly the impact,” he admits.

“But I know it will be a lot. I’m connected to startups and changemakers across Africa. A lot is brewing. We want to be the catalyst that helps these organizations see the light of day.”

What advice would you give to others?

His advice is deceptively simple: just start.

“It might look like the advice doesn’t make sense, but everything great today started somewhere with a simple step,” he says.

“You won’t know all the steps on the first day, but you’ll know the step you’re supposed to take today.”

For him, courage is the missing ingredient for many. He doesn’t want to reach 60 or 80 years old and look back with regret. “I want to be able to say, I did all I could with what I had.”

He warns that hesitation carries its own risks.

“Whatever idea you’re thinking about, someone else is probably thinking about it too. If you don’t do it, one day you’ll see them doing it. So take the first bold step, and everything will be fine.”

Contact or follow Dr. Gozie Ezeh:

Leave a comment and follow us on social media for more tips:

- Facebook: Today Africa

- Instagram: Today Africa

- Twitter: Today Africa

- LinkedIn: Today Africa

- YouTube: Today Africa Studio