Motorcycle taxis are the backbone of everyday mobility across African cities.

They move millions of people and goods each day, but they are also expensive for riders to run, volatile in income, and deeply polluting. Fuel costs eat into earnings. Maintenance is constant, and for many riders, stability is always just out of reach.

Spiro entered this system with an unusually ambitious proposition. Replace petrol motorcycles with electric ones, build a continent-wide battery swap network, and make clean mobility work for informal workers at scale.

Backed by industrial and development capital, the company has expanded rapidly across West and East Africa, positioning itself as one of the most aggressive climate-tech plays on the continent.

This inside Spiro’s journey traces the founding story, their funding journey, strategic moves, societal impact, challenges, and lessons learned.

Disclaimer: Based on publicly available information as of February 2026 from reliable sources such as TechCrunch, Rest of World, CleanTechnica, mobility industry newsletters, and Spiro publications.

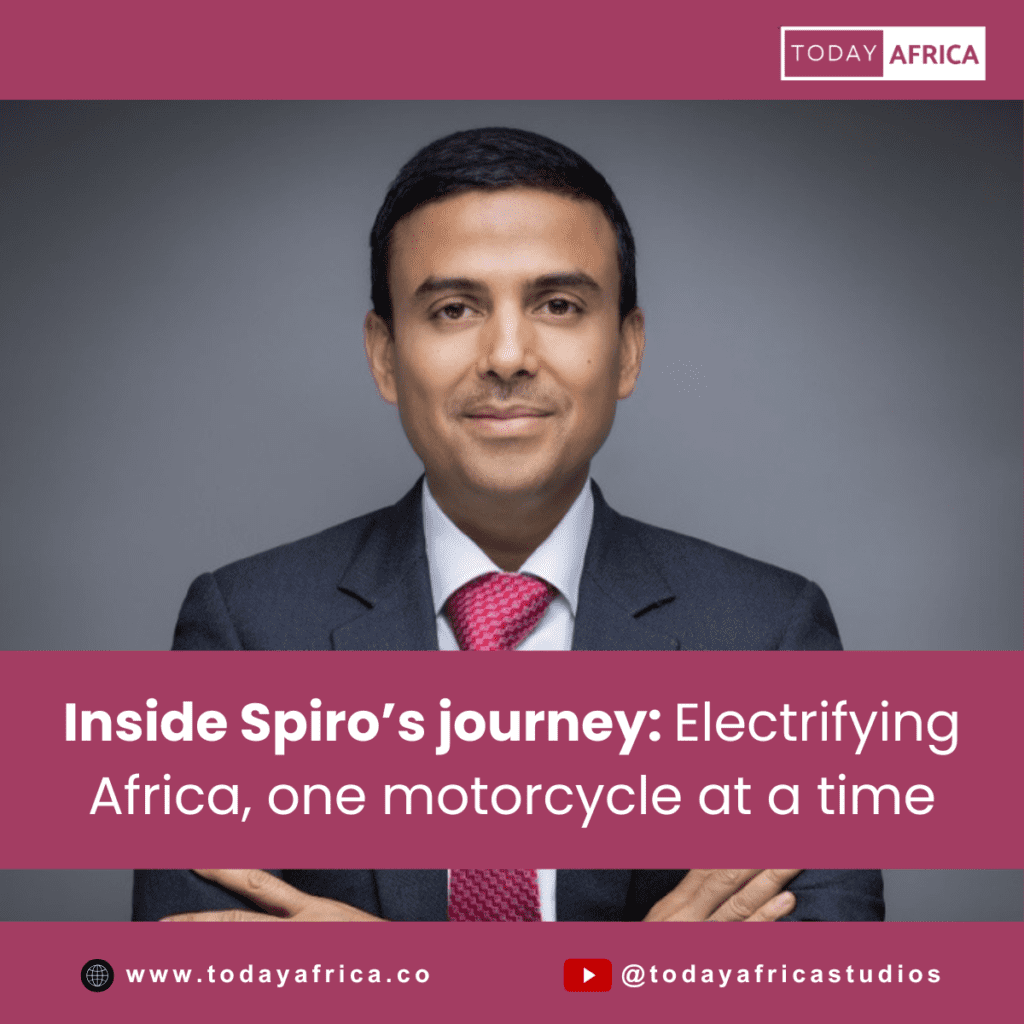

Founding story of Spiro

Spiro began life in 2019 (as M Auto Electric) under the aegis of Gagan Gupta’s Arise/Equitane investment vehicles, with a mission to tackle Africa’s ubiquitous motorcycle-taxi problem with green technology.

Its founders, led by Indian entrepreneur Gagan Gupta (CEO of infrastructure investor Arise) and later CEO Kaushik Burman (ex-Gogoro), saw that African cities rely on millions of moto-taxis to transport people and goods.

Roughly 30 million riders work long hours ferrying passengers on two-wheelers, collectively spending an estimated $30 billion a year on petrol. This creates a brutal cycle: drivers often walk away with only a third of their fare after paying for fuel and repairs, while streets fill with exhaust and noise.

Spiro’s founders believed electric motorcycles, powered by a novel battery-swap network, could slash costs for drivers and emissions for cities.

Founded in Benin (West Africa) and seeded by Arise’s Africa Transformation and Industrialization Fund (ATIF), Spiro spent its first years prototyping in Benin and neighboring Togo.

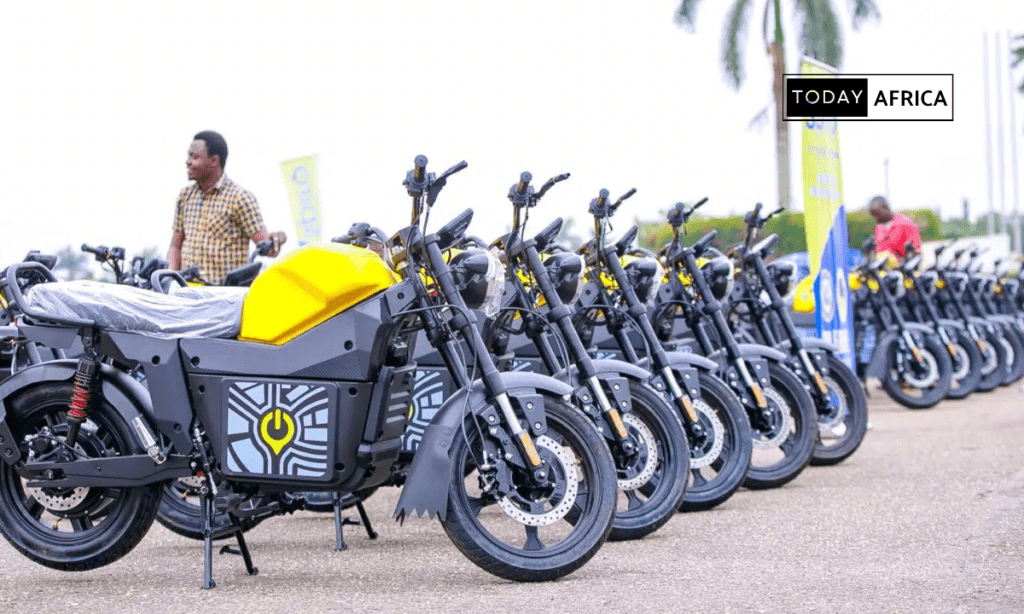

In 2019–2022, it exchanged thousands of old petrol bikes for new electric models at no upfront cost to riders. (Riders paid only a daily fee for battery swaps, covered maintenance, then earned ownership after sufficient use.)

By early 2024, Spiro had placed over 10,000 e-bikes on African roads across Benin, Togo, Rwanda and Kenya. This rapid scale owed much to its deep pockets and vision.

As co-founder, Gagan Gupta later explained, Spiro aimed to “reduce the import bill” by slashing drivers’ operating costs about 30%, even partnering with African pop star Davido in 2025 to brand “Made-in-Africa” e-bikes for young riders.

Spiro’s launch coincided with a growing push for EVs in Africa. Rwanda banned new registrations of petrol motorcycles from 2025, and Kenya removed VAT/duties on electric two-wheelers.

Those policy signals suggested a chance for a cleaner, cheaper moto-taxi. Spiro therefore positioned itself at the crossroads of climate tech (CO₂ cuts), mobility (replacing gas bikes), energy (reliable battery infrastructure) and informal labor (supporting drivers’ incomes).

Its early pilots tested this model on crowded city streets, engaging skeptical riders by highlighting savings. One Beninese driver, Dandao Simon, reported that after switching to a Spiro e-motorcycle he no longer had fuel or oil costs, meaning “all that money going to repair is now mine”.

By building dozens of swap stations in Cotonou and other cities, Spiro addressed the charging gap: riders simply pull up, hand in an empty battery and get a fresh one in minutes (a concept pioneered by Gogoro in Taiwan but adapted to African needs).

Throughout 2022–2024, Spiro quietly laid this foundation while navigating regulators and communities. It educated drivers about the tech and worked with officials on safety and licensing (even as policy regimes were still in flux).

By mid-2025, Spiro could claim it was powering a continent‑wide electric motorcycle ecosystem, 60,000+ bikes and 1,200+ swap stations across six countries. These figures and recognition, like a TIME 100 Most Influential Company award in 2024, underscored its audacious growth.

Funding history, investors, year & purpose

From the start, Spiro was capital-intensive. It was backed by deep-pocketed industrial investors rather than traditional Silicon Valley VCs.

In its earliest phase (2019–2022), Spiro was largely funded by Gagan Gupta’s Equitane/ATIF network. By 2025, Spiro had already raised well over $180 million of equity and debt from Equitane and Société Générale alone.

Key funding milestones include:

- 2019 (pre-launch): Seed backing by ATIF/Equitane (Arise). Founding funding reportedly totalled on the order of tens of millions (Wikipedia cites $85M), allowing Spiro to prototype its swap model in Benin and Togo.

- Aug 2023: Spiro secured a $63 million loan deal (roughly XOF 37.8 billion) from the Société Générale banking group (via its Benin/Togo arms). The facility, backed 70% by GuarantCo, was explicitly designed to expand the fleet in Spiro’s home markets. Spiro’s co-CEO Jules Samain said this financing would add “15,700 clean electric motorbikes, over 31,400 batteries and more than 1,000 swap stations” to its existing network.

- May 2024: A $50 million debt facility from Afreximbank (Heads of Terms announced at Africa CEO Forum 2024). This Pan-African bank funding (asset-backed debt) was intended to “accelerate [Spiro’s] operational capabilities”, specifically scaling swap stations and bringing new bike models to market. The deal was celebrated as Afreximbank’s commitment to green innovation.

- Oct 2025: A record $100 million round led by the Fund for Export Development in Africa (FEDA), the impact-investment arm of Afreximbank. This is reported as Africa’s largest-ever investment in the EV sector. The cash is earmarked for an aggressive rollout building more battery-swap infrastructure (targeting 100,000 bikes by end-2025) and deepening Spiro’s technology and manufacturing platform.

Each funding tranche had clear uses. The SG/GuarantCo financing accelerated Spiro’s Benin/Togo rollout, while the Afreximbank debt was to expand across East and West Africa and introduce new models.

In public comments, Spiro executives emphasized that these funds would “expand [the] network of automated swap stations and introduce new electric bike models, enhancing accessibility of green mobility”.

Investors from climate-focused development banks to industrial holding groups were drawn by Spiro’s combination of social impact and scale.

In a tough mobility market, Spiro’s promise of cost-saving technology (plus near-term revenue from swap fees) and alignment with carbon-reduction goals made it stand out.

Compared to earlier African mobility startups (many of which sought only hundreds or thousands of bikes), Spiro’s capitalization was on a different order, a testament to investor confidence in its ambitious model.

Read Also: Inside Wasoko’s Journey: Transforming Access to Essential Goods and Services

Strategies fueling the growth of Spiro

Spiro’s expansion has been powered by a few core strategic pillars:

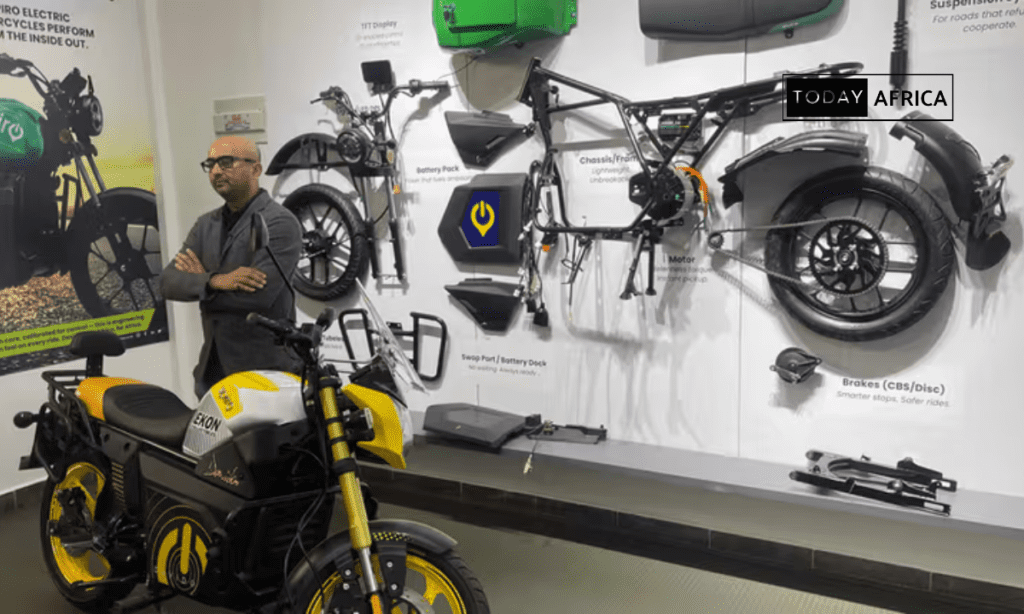

1. Battery-swap infrastructure

Spiro built a continent‑wide swap network from Day 1. Riders buy or lease a Spiro bike, but Spiro retains the battery. Instead of charging overnight, drivers stop at one of Spiro’s swap stations, slide out a spent battery and instantly get a charged one.

This model overcomes Africa’s lack of charging infrastructure: swapping takes only minutes, meaning drivers don’t have to idle or risk long charging delays. It also lowers upfront costs; a Spiro e-bike (with battery service) sells for roughly 30–40% less than an equivalent petrol bike.

In practice, riders simply pay a flat daily fee ($3–$5 USD in local terms) for up to a set number of swaps (typically 7 swaps/day), which covers insurance and maintenance. After extensive use (e.g. 150,000 km on the swap plan), riders become full owners of the motorcycle and can stop paying the daily fee.

This service-led asset model is a linchpin of Spiro’s growth: it quickly seeded thousands of vehicles on the road (at Spiro’s expense) while creating recurring revenue from battery usage.

2. Ride economics

The model has a clear pitch to drivers. By driving a Spiro e-bike, a rider saves on fuel and maintenance. Spiro itself estimates a driver can save roughly $360 per year compared to a petrol bike.

TechCrunch reports an e-bike’s cost-per-kilometer is about 30% cheaper than gas. Riders like Cotonou’s Dandao Simon testify that no more money goes to repairs or petrol on Spiro bikes.

In effect, drivers “get to take home more” of each day’s fares. This value-for-money message has been central to Spiro’s branding: it markets not just climate credentials but hard cash savings to the informal workforce.

3. Geographic rollout

Spiro has expanded in phases. It started in Francophone West Africa (Benin, Togo), where it could leverage founder connections. With initial success, it moved into East Africa’s big markets (Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda) and also Nigeria.

Country selection factors included: high two-wheeler usage, emerging EV policies (e.g. Rwanda’s bans, Kenya’s subsidies), and the presence of entrepreneurial partners.

For example, after proof of concept, Spiro secured a Uganda government partnership to convert hundreds of thousands of boda-boda taxis to electric and joined Kenya’s national EV push (targeting over a million EVs).

Urban density also matters. Spiro focuses on cities where petrol stations are numerous, but EV support is limited. Often, Spiro will begin by capturing a niche (e.g. delivery companies or taxi associations) then broadening.

Crucially, it commits to local assembly to reduce costs: by 2025, it had built assembly plants in Benin, Togo, Kenya and announced factories in Rwanda, Nigeria and Uganda.

These factories (the Kenya plant alone can make 50,000 e-bikes/year) not only cut import costs but strengthen Spiro’s control over specs and supply.

4. Partnerships

Spiro has aggressively partnered at every level. It negotiated with governments for supportive frameworks (Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria) and secured media-friendly deals, for instance, a collaboration with East African churches in Kenya to site solar-powered swap stations on parish grounds.

It aligned with local businesses: in Nigeria, it teamed up with Zoome and The Sun to distribute e-bikes. In 2025, Spiro even hired Afrobeats icon Davido as a brand ambassador, unveiling limited-edition “Davido Collection” e-motorcycles at an Africa CEO Forum event.

Academically, it is linked with Mount Kigali University to install swap stations on campus and train EV technicians. These partnerships serve multiple purposes: they broaden Spiro’s network (e.g. using church land speeds station rollout), embed the company in local industry and community, and boost marketing.

By contrast with earlier small startups, Spiro’s ecosystem approach is holistic: it sees itself not just as a bike-maker but as a mobility platform (even piloting a Spiro ride-hailing app and financing plans for drivers).

5. Branding and positioning

Spiro sells itself as a climate champion. Its messaging, “Made in Africa by Africans”, emphasizes local industrialization. In 2024, it earned a TIME 100 nod for its social impact.

The company ties into UN Sustainable Development Goals (clean cities, climate action) and highlights quantitative impacts (kilometers electrified, CO₂ saved) in press releases.

This appeal to investors (and riders proud to be part of a green transition) complements the cost savings pitch. Compared to earlier two-wheeler ventures, Spiro has combined hardware + service + social mission in its brand, a full-stack clean mobility approach that resonated with impact-oriented backers.

6. Energy infrastructure

Beyond bikes, Spiro is building power assets. Its swap stations are grid-powered but designed to integrate solar. It already opened solar swapping hubs (one in Nigeria, and a plan in Kenya at Catholic churches) to cut energy costs.

In effect, Spiro is creating a decentralized, smart battery network. This strategy not only reduces its carbon footprint (and electricity bills) but may allow Spiro to sell grid services in future (e.g. balancing renewable energy with mobile storage).

Read Also: Inside mPharma’s Journey: Fixing Pharmacy Supply Chains at Scale

Competition in the mobility and climatetech ecosystem

Spiro’s rise has stirred competition on several fronts.

1. Local EV startups

A new wave of African e-bike firms has emerged, but none match Spiro’s scope. Competitors include Rwanda’s Ampersand (the first African e-moto startup, with several thousand bikes), Nigeria’s ARC Ride and Zemo, and Ethiopia’s Dodai.

These firms also sell electric motorcycles, and some offer swapping or battery subscription. However, Ampersand’s model (leasing batteries to owners) and Zemo’s (selling e-bikes to riders) remain more limited in scale.

Roam, a Kenyan startup, makes e-buses and e-bikes, but on far smaller deployments. Spiro’s advantage is sheer network size: by late 2025, it touted 60,000 bikes and 1,500 swap stations continent-wide, compared to Ampersand’s few thousand.

Furthermore, Spiro’s backing, including debt finance from Afreximbank, has let it expand faster than its rivals.

2. International entrants (limited)

Few global EV giants have entered Africa’s two-wheeler market. Asian companies like Gogoro or Niu have proven swap-bike concepts at home, but have not launched African operations. (Indeed, analysts note Gogoro’s self-service swaps aren’t practical here, where riders expect attended stations.)

Chinese EV firms are watching: Transsion (maker of Infinix phones) has recently unveiled a scooter brand, TankVolt, targeting Nigeria and other markets. But these efforts are nascent.

Spiro’s partnerships with Chinese OEM Horwin for bike imports show it has more international integration than some local startups, but Spiro still largely buys its bikes and batteries from Asia.

In contrast, legacy motorcycle assemblers (Yamaha, Bajaj, Honda, etc.) dominate the gasoline market, mostly selling inexpensive ICE bikes and spare parts via vast dealer networks. Those incumbents remain Spiro’s real competition for drivers.

3. Indirect (petrol bikes)

Spiro’s own management emphasizes that “our competition is the gasoline bike segment”, not fellow EV startups. A typical petrol moto can cost as little as $600–$800 secondhand.

Spiro’s EV may be cheaper to run, but it still commands a higher upfront (or daily) payment. Millions of petrol motorcycles, both new and imported used, are deeply entrenched, with established repair shops and fuel stations.

Persuading riders to switch requires matching or beating those economics. The second-hand market is also fierce: drivers often choose decades-old, bona fide “dealer” bikes for reliability.

In this sense, Spiro’s competition is diffuse: every unconverted rider and every non-networked bike represents lost market share.

4. Moats vs. pressures

Spiro’s answer to competition is scale and integration. Its extensive swap network and local assembly plants create a high barrier to entry for challengers. Constructing 1,200 stations across a continent is capital- and logistics-intensive.

By controlling the batteries and software, Spiro also builds a proprietary data and maintenance system.

These assets are its moat, making it harder for smaller rivals to replicate. On the other hand, Spiro faces immense cost and supply-chain pressures.

The batteries themselves are largely imported (mostly NMC/LFP cells from China), and experts caution about “extremely difficult” market agility if demand spikes.

Maintenance and theft risk loom large, too: company-owned bikes can be stolen or damaged since drivers don’t fully own them initially. Currency shocks (e.g. Nigerian naira devaluation) can suddenly inflate import costs. Such pressures narrow profit margins.

Read Also: Inside InstaDeep’s Journey: From Two Laptops in Tataouine to a $682M Acquisition

Impact on society and the environment

Beyond corporate metrics, Spiro is already reshaping communities and the climate:

1. Rider economic impact

Spiro’s e-bikes demonstrably put money back in drivers’ pockets. By replacing petrol consumption with electricity, a driver can save roughly $3–$5 per day, amounting to about $360 annually.

As CleanTechnica reports, riders who swapped to Spiro now “get to take home more” of their fares. For example, in Kigali, one moto-taxi driver, Ange Uwingeneye, says she now earns 15,000 RWF/day, far above what she used to net on petrol.

These savings stabilize incomes for informal workers, making livelihoods more sustainable. Over time, many riders transition from lessee to owner of their bike (after the 150,000 km threshold), building equity and assets that were impossible under continuous fuel leasing.

2. Environmental benefits

Every electric kilometer displaces a liter of petrol. By late 2025, Spiro’s network had powered hundreds of millions of zero-emission kilometers.

Official reports cite roughly 800 million km of low-carbon travel, which CleanTechnica translates into on the order of tens of thousands of tonnes of CO₂ avoided (33,000 tonnes by mid-2025). Local air quality improves as tailpipe fumes vanish from dense city corridors.

In addition, Spiro’s emphasis on renewable energy (solar charging hubs) means each swap station can become a mini solar power plant. For instance, Spiro’s solar swap installation in Nigeria and planned solar stations at Kenyan churches exemplify how its charging infrastructure also adds clean generation capacity.

3. New energy and jobs ecosystem

Building Spiro has created a local industry. The company now operates four assembly plants (in Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, and Nigeria).

These factories retooled from existing facilities employ thousands of workers (over 1,000 direct and indirect jobs reported). Spiro is also cultivating suppliers: it has begun locally assembling electric motors and controllers in Kenya, and plans to scale to frames and batteries once volumes justify it.

This industrial footprint helps kickstart Africa’s clean manufacturing sector. On the operations side, Spiro’s swap network hires local station operators and technicians; rider incentives (like Spiro Academy and university partnerships) are training an EV-savvy workforce.

By mid-2025, the company claimed 35,000 bikes on the road, 20 million battery swaps completed, and over half a billion kilometers ridden. If realized sustainably, these gains hint at a new mobility paradigm.

Read Also: Inside VIEBEG Medical’s Journey: Using Data to Transform Africa’s Medical Supply Chains

Challenges Spiro has faced

Spiro’s success has not come without hurdles. The most acute challenges include:

1. Regulatory uncertainty

African governments are still figuring out EV policy. While some (Rwanda, Kenya) have been proactive, others lack clear e-mobility regulations or incentives.

Spiro must therefore negotiate entry market by market, dealing with inconsistent rules on vehicle safety, import taxes, or grid access. For example, switching moto-taxis to electric often requires aligning with taxi unions and meeting local licensing rules.

In some places, charging a battery could be classified as selling electricity, triggering utility tariffs. Spiro has thus spent significant effort on advocacy and pilot agreements (like its Ugandan government pact) to shore up each market’s regulatory support.

2. Capital intensity

As Spiro itself and analysts note, the model burns money quickly. The Rest of World investigation estimated that Spiro had already used over $143 million just to field 10,000 e-bikes.

The CEO admitted another $100+ million would be needed for the next 10,000 bikes. In concrete terms, building stations and pre-financing vehicles requires huge up-front capital.

This creates enormous cash burn; Spiro may invest $150 million of capex per country to reach meaningful scale. Even though debt (like the $50M Afreximbank loan) and equity have funded expansion, the underlying unit economics are thin.

An analyst warned, “if the failure of Bird is anything to go by, then this seems like another high-growth, high-loss startup”. Spiro’s profitability is distant; each bike’s cost must be amortized over many years of fees. Any hiccup in funding could severely slow growth.

3. Supply chain risks

Spiro’s bikes and batteries come largely from China. This creates vulnerability. Global battery prices or supply disruptions (e.g. raw material shortages, China export controls) can instantly raise costs.

Experts caution that stocking hundreds of spare batteries ties up capital and risks degradation: idle lithium batteries lose capacity if not cycled regularly. During a surge in demand, Spiro might scramble to import more cells.

Conversely, if growth stalls, Spiro could end up with excess batteries aging in warehouses. No easy local substitute exists yet, so Spiro’s fortunes remain linked to international EV component markets.

4. Operational complexity & rider adoption

Running a vast swap network is logistically challenging. Each station needs reliable power, trained staff, and an inventory of batteries. In some cities, Spiro has struggled with queue management and maintenance (e.g. keeping all batteries healthy, fixing bikes promptly).

Theft and vandalism also occur: since Spiro owns the bikes until they’re paid off, some drivers have little incentive to safeguard them. Indeed, Rest of World reporters observed abandoned old bikes (collected from swaps) scattered in yards, evidence that a second-life plan for those assets has failed.

On the user side, changing habits is hard. Some tech-savvy riders have gamed Spiro’s system (buying old bikes cheaply just to trade for a free Spiro bike). Spiro has already begun ending its no-cost exchange offer for new drivers to curb such exploitation.

Trust is another barrier: drivers worry whether batteries will work, if stations will always have charge, or if Spiro will remain in business. Convincing informal workers to adopt an unfamiliar service model requires sustained outreach and marketing.

5. Macro and internal pressures

Spiro operates in volatile currencies (CFA franc, naira, shilling) while costs (like batteries) are US-dollar priced. Currency devaluations can widen losses sharply.

Inflation or fuel-price changes in Africa also affect rider economics (for instance, a spike in petrol makes Spiro more attractive, but if diesel was subsidized and suddenly removed, public backlash can ensue).

Internally, scaling a company from a few hundred to thousands of employees across multiple countries tests management bandwidth. Recruiting skilled staff for EV tech in Africa, a nascent field, has proven tough, so Spiro often brings in expatriate trainers or partners with local universities.

Read Also: Inside Twiga Foods’ Journey: From Rural Farms to Cities

Sustainability, risks, & open questions

Looking ahead, the biggest question is whether Spiro’s model can sustainably scale.

On one hand, the company has demonstrated that massive investment can electrify a large share of moto-taxis: it now claims it is Africa’s largest EV mobility firm, with 800 stations and 40,000+ e-bikes deployed.

If rider demand keeps growing, each additional bike generates revenue for years. The climate benefits and job creation serve the public good, aligning Spiro with African development goals.

On the other hand, the economics remain precarious. Unit costs are high (billions in capex) and must eventually be covered by either rider fees or new financing. This is partly by design; Spiro deliberately subsidized adoption in its early years. But the burn rate cannot go on indefinitely.

Financially, Spiro will need to get much closer to break-even on each bike or secure continuous cheap debt. Any tightening of global funding for emerging markets (e.g. rising interest rates) could expose Spiro to liquidity crunches.

Battery lifecycle is another issue. Spiro’s model depends on batteries being cycled many times. Over 5–7 years, batteries will degrade and need replacement, at considerable cost. How Spiro manages end-of-life recycling or swapping old packs for new ones will test its long-term viability.

Additionally, if governments back away from EV incentives (say a new administration reprioritizes diesel fuel subsidies), Spiro could lose advantages it has relied on.

Comparisons to other mobility ventures are instructive. The collapse of scooter-rental companies in the U.S. showed how high-growth models can quickly become unprofitable.

In Africa, even Ampersand, which had a 70% share of Rwanda’s market, has only a few thousand bikes after six years, highlighting how hard full mobility transformations are.

Nigerian e-moto startups like MAX.ng shifted back toward cars when bikes proved tough to scale. In that context, Spiro’s success is neither guaranteed nor easily replicable without its extraordinary backing.

Ultimately, what Spiro must get right is careful scaling and cost control. Unit economics should improve as local assembly and battery factories come online (Spiro is building a battery plant in East Africa in 2024).

Keeping adoption rates high is crucial: the more swaps per battery, the better the return. Spiro also needs to expand into newer revenue streams (for example, selling power back to the grid with its batteries, or servicing corporate fleets).

Read Also: Inside Wave’s Journey: Francophone Africa’s First Unicorn

Conclusion

Spiro’s story is a test of African climate-tech ambition. It embodies a bold vision: that Africa could leapfrog directly into clean mobility by embracing two-wheel EVs at scale.

If Spiro succeeds, converting millions of drivers to electric and building a self-sustaining battery economy, it could signal a turning point.

- Policymakers would see that industrial-scale EV networks can work on the continent, inspiring more supportive regulations and local manufacturing incentives.

- Investors would gain confidence that Africa can absorb huge climate-tech capital with real returns.

- Entrepreneurs would learn that combining social purpose with robust partnerships can create pan-African businesses.

But Spiro’s story also underscores fragility. Its very existence relies on continuous external funding and a stack of favorable conditions. Were any link in that chain to break, Spiro’s expansion might stall, and African riders could be left stranded with a half-built system.

As of late 2025, Spiro can point to concrete results (half a billion zero‑emission kilometers logged, thousands of families helped, new green factories opened).

Whether it heralds a sustained green revolution or remains a one-off ambitious experiment is yet to be seen. But it has undeniably raised the bar for clean mobility on the continent.

In the coming decade, Africa will watch closely whether Spiro’s network becomes an indispensable utility, or a cautionary tale about how hard it is to make mobility truly sustainable.

Sources: Author interviews, press releases and news reports from TechCrunch, Rest of World, CleanTechnica, mobility industry newsletters, African business media, and Spiro publications.

Leave a comment and follow us on social media for more tips:

- Facebook: Today Africa

- Instagram: Today Africa

- Twitter: Today Africa

- LinkedIn: Today Africa

- YouTube: Today Africa Studio