When most people think of tech in Africa, they imagine apps, startups, and big city offices. But for Richard Afolabi, it’s always been about more than the latest innovation; it’s about shaping a future where technology meets identity.

Leaving behind the comfort of predictable tech roles, he founded Bekkah AI, a company built to explore what technology can do for Africa, while preserving the continent’s stories and history.

Richard’s journey is anything but typical. From software to hardware, from marketing campaigns that generated millions to products that barely survived their first week, he has navigated every side of the tech world.

But it was his curiosity about Africa’s potential and his drive to hold onto its memory that led him to create something entirely new.

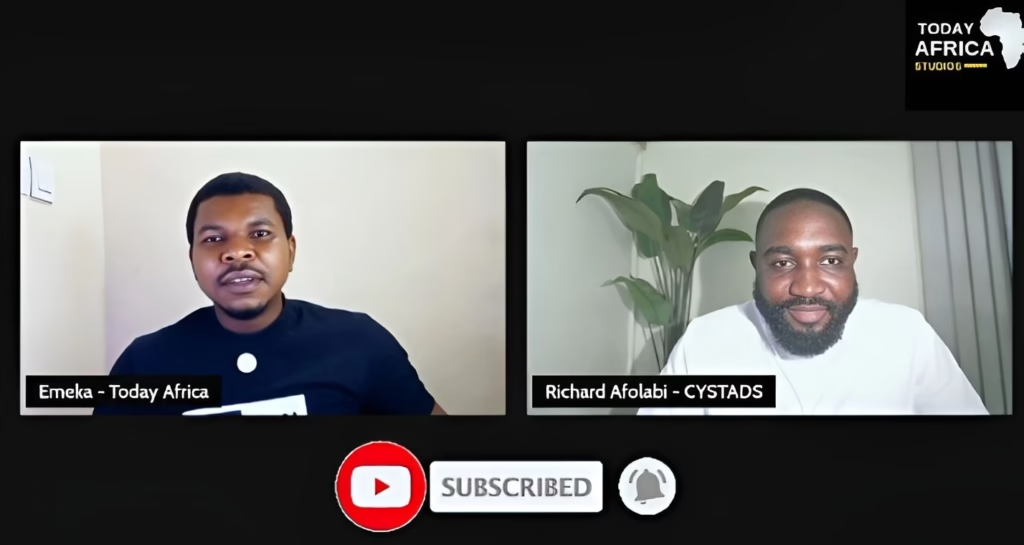

In this exclusive interview with Today Africa, Richard Afolabi opens up about his startup, the challenges of building tech for a continent, and why the future of Africa depends on knowing our history and identity.

Who is Richard Afolabi?

Richard Afolabi discusses the dual passions that define him: technology and storytelling.

“What I do is help people solve their tech problems,” he says. “Whatever tech problem you have, basically, I’ll find a solution to it.”

With over a decade in the technology industry, Richard has honed his craft in both software and hardware, but he insists that staying updated with industry trends is only half the equation.

He is equally obsessed with marketing. “You have anything that can change the world, it’s also your duty to ensure that it gets to the people that would use it,” he says, paraphrasing Steve Jobs.

For Richard, an idea alone is not enough; it has to reach the people who can leverage it. Storytelling, he argues, is integral to success, not just for products but for people.

“I wrote something in my study this morning about International Men’s Day,” he adds, reflecting on the importance of narrative in shaping recognition.

“If it were a woman’s affair, we would have it everywhere. Men, our ego won’t let us celebrate ourselves, but it’s because we don’t tell our stories. Men should tell their stories, not for sympathy, but so people understand what it feels like to be a man in this world right now.”

Outside of work, he dabbles in hardware engineering, constantly exploring new ways to solve problems and push boundaries.

Tell us more about Bekkah AI, the products, and the services

Bekkah AI was born from a restless mind during a period of personal and professional upheaval.

In January 2021, Richard resigned from his position as head of IT at an Agritech firm, a decision spurred not by dissatisfaction but by a desire to tackle increasingly complex challenges.

“When I conquer this level of problems, I look for a new one that is more difficult and inspiring,” he explains.

His time at the Agritech company was intense. He led both IT and marketing campaigns, launching a team called IMCT that raised $10 million in under a year, a feat that rippled across agritech companies nationwide.

But the pace was grueling, and Richard wrestled with mental health challenges during that period. “At one point, I was through Polar Disorder because it was crazy. The highs and the lows were really intense.”

After leaving, he took time to recharge, but idleness was never an option.

It was during this reflective period that Bekkah AI emerged, initially sparked by a project called CYSTADS, a platform designed to help Africans reconnect with their past through data collection.

“Nobody will give you money for ideas. People only give you money when they see traction and impact,” he says bluntly.

Starting the company was not easy. Richard had only about N1,500 left in his account after registering the business. “The first six months were very difficult,” he recalls. But luck, he believes, favours preparation.

Within six months, Bekkah AI generated $100,000 in revenue, consulting for international firms and gradually expanding into a training institution, Bekkehdemia, to equip African youth with tech skills.

Richard had been ahead of the curve, incorporating AI into Bekkah’s mission even before the technology became mainstream.

“We saw the trend that this would change a lot of things. Some people saw it before it happened and aligned with it,” he explains.

Bekkah AI became both a consulting firm for revenue generation and a platform for Africans to engage with AI and technology in meaningful ways.

CYSTADS, the cultural and historical archive, remains central to the mission. “Most Africans don’t know who they are,” Richard says.

“If they knew their past, the trade routes, the systems, the achievements, they wouldn’t rely on others to save Africa. Europe and America have their own problems; they won’t save us. We have to save ourselves.”

How do you raise $10 million for the Agritech firm and $100,000 for Bekkah AI?

“It’s easier said than done,” Richard begins, emphasizing the invisible labor behind these numbers.

The fundraising for the Agritech firm happened during the 2019–2020 COVID panic, a period when many Africans in the diaspora were reconsidering returning home.

He leveraged that moment with a meticulous integrated marketing strategy spanning print, digital, and offline channels. “The campaign was airtight,” he says.

Luck, he stresses, is preparation meeting opportunity. The $10 million was raised in less than a year, but only after four years of underground groundwork.

The same principle applied to Bekkah AI. In the first six months, traction was minimal.

“People knew me from my Agritech days; they trusted me with their projects. That word-of-mouth helped us get clients, including deals with the Central Bank of Liberia,” he explains.

Richard’s philosophy is grounded in usefulness: even when he feels used, he sees it as a form of skill acquisition.

“For you to be used means you are useful,” he says. This mindset, coupled with obsessive attention to detail, has been central to his success.

Read Also: Niza Aritha Zulu: From Student Idea to Patent-holding Agritech Innovator

What inspired you to believe that Africans need technology to preserve their history and identity?

Richard’s own genealogy shaped his vision. He comes from a large, diverse family spanning West Africa, from Ivory Coast to Ghana, Togo, Benin, and Nigeria.

“It’s easier for me to say I’m West African than just Nigerian,” he notes. DNA analysis would reveal a mix of ancestries, further feeding his curiosity about cultural diversity.

This awareness crystallized into a conviction: identity is essential for progress.

“If you or your people don’t have an identity, you’ll lose yourselves in the struggle for survival,” he asserts.

Richard rejects the pervasive “hustle” mentality, preferring the word “thriving” instead. Survival keeps people consuming; thriving allows them to create.

His mission is deeply historical. Richard points to African achievements that rivalled Europe centuries ago, streetlights in Benin before European cities had them, complex immigration systems in Libya, and architectural feats dismissed by biased narratives as alien-built.

“For Africans to move forward, they need to know where they are coming from,” he says.

Technology, he argues, is the tool to preserve and extend this knowledge. AI, digitization, and modern systems can ensure Africa’s history survives and inspires future generations.

“Most of the things we have in Africa, like Timbuktu, if they’re not digitized, they won’t exist any longer,” he says. Technology, unlike humans, is impartial, it preserves, scales, and pushes progress.

For Richard, connecting Africans with their roots is not just cultural, it’s foundational for empowerment.

“When Africans know themselves, they can start solving their own problems. When they start solving their own problems, they can start solving the world’s problems,” he said.

How do Africans move from consumers to producers?

Richard Afolabi sits back, a half-smile forming, as if he’s replaying a mental movie.

“Everything a man is or would ever be starts from his mind,” he begins, his voice steady but charged with urgency. “Till the mind is wired towards something, you most likely make the choices that are required to change your situation.”

For Richard, this wiring isn’t abstract theory; it’s a principle he has lived and observed in the world around him.

He calls it the priming principle. “The idea behind priming is simple,” he says.

“If I want you right now to move from wherever you are to, say, Dubai, and I ask you outrightly, ‘Would you move tomorrow?’ you might say yes, maybe because Dubai seems appealing.

But if I say Libya or Sudan, your first instinct is no. And that’s because your mind hasn’t been primed to see opportunity there.”

Priming, he explains, is about repetition, exposure, and subtle persuasion.

“You start telling someone nice things about Libya, the opportunities, the resources. You repeat it for months. And then, when you ask again, they say yes. Because you’ve changed their perception.”

For Richard, this principle applies to Africa itself. “Most of us think our minds are strong-willed, but it takes maybe exposure 100 to 1,000 times to shift perception. That’s why the media is such a powerful tool.”

He leans forward, eyes narrowing. “Look at Nigerian legacy media, they push frivolous stories. VDM and Mr Jollof fighting on a plane, how is that nation-building? There are more pressing issues for young people.”

He gestures broadly. “I don’t have a problem with Big Brother Nigeria, but imagine the impact if the money spent there went into infrastructure, sports, or industry. Nigeria has the youth, the talent, the audience, but we fail to prime them for building businesses or thriving careers.”

Richard is not just analyzing problems; he’s dissecting the failure to intentionally prime a generation.

“We have to expose young people to history, to culture, to the successes of those before them. That’s how you change mindsets from survival to thriving. If we want African youths to become producers instead of consumers, we must prime them deliberately.”

Related Story: Why Joan Kembabazi Won’t Stop Fighting Child Marriage in Uganda

Why do you believe heritage is a technology problem?

Technology, to Richard, is not merely a tool; it’s a lever for survival and legacy.

“Technology allows you to reach more people,” he says, his tone almost conspiratorial. “If I want data from a remote community in Akwa Ibom, I don’t have to go there. I don’t have to send anyone. People can gather and preserve information digitally.”

He gestures to the invisible expanse of Africa’s disappearing languages and traditions.

“Right now, as we speak, languages are dying. Some have fewer than ten speakers left. Young people aren’t recording these things because survival takes precedence. Technology is the muzzle, the core thing, the enabler to solve this problem faster.”

Heritage, he insists, is not static; it’s a living system that requires deliberate preservation, and technology is the only way to safeguard it before it vanishes.

CYSTADS says: Reclaiming our Story. Reconnecting our Roots. What does this mean for someone who feels disconnected from his family lineage?

Richard leans back, clasping his hands.

“If you feel disconnected from your roots, it’s a sign that you’re seeing yourself as an individual, not as part of a community. Community is the base of every thriving society. Look at Elon Musk building SpaceX, it’s on the back of community, people coming together to create something that lasts. That’s how civilizations are built.”

He counts generations, painting a picture of human continuity.

“For me to exist, my parents had to come together… We are the product of collective effort. Africans have lost this perspective. We need to connect with our past and present collectively to understand our potential.”

Richard’s voice rises with intensity as he explains the tangible benefits of understanding one’s lineage.

“From my mother’s side alone, I have about 45 uncles and aunties. If each has an average of two children, that’s 90 people. If we face a problem costing $150,000, that’s just $1,000 each. Because of the community, we can solve issues internally before looking outside.”

He stresses the psychological impact too.

“Understanding your roots transforms you from victim to victor. If your ancestors survived the slave trade or resisted oppression, it means resilience runs in your veins. Africans need to see themselves as a collective force, not isolated units. Only then can we reclaim our story and start building real power.”

Read Also: Meet Emmanuel Osemudiame, the Doctor Using Tech to Fight Mortality in Nigeria

How can someone use CYSTADS to preserve their family story, history or identity?

Richard Afolabi leans forward, eyes lighting up as he describes a world where ancestors speak again.

“I’ll start from the basics,” he says, a wry smile tugging at the corner of his mouth. “The basics are some of the AI tools we have currently.”

At its core, CYSTADS begins with something simple: images.

“With our AI tool for image,” he explains, “you can take a picture of your ancestor, maybe a picture that’s not clear, maybe one that is, and create a clearer image of that ancestor.”

“You can recreate images of your ancestors that nobody knew. Now you can put a picture on their face. You know, this is what this person looks like,” he says.

Then there’s the voice. AI transforms static images into speaking models, animating history with words.

“We now take those images and use AI to lip sync to create a model of their voice. So you can now listen to your ancestor as your ancestor is or was in real time and tell the stories of your family history that you’ve been able to gather over a period of time.”

Listening to these voices, children and families experience the past intimately, not as a distant fact but as living memory.

CYSTADS doesn’t stop at family stories. It ventures into the landscapes of history, blending augmented reality with virtual reality.

“We’ve mapped about 20% of the largest city in West Africa with augmented reality. Meaning that when you are in that city, you can easily walk up to a statue, a historical building, and scan from our app and talk to that historical statue or learn from that historical building.”

He recalls Efunsetan Aniwura, a powerful woman in Ibadan’s history.

“When you see her statue there, she has a broken leg. But we used AI and AR to bring it back to life. Point your phone at it from our app, and she will talk to you about her story. Then it redirects to our website to read more about her.”

For Afolabi, these tools aren’t merely digital curiosities, they are a bridge for Africans in the diaspora, many of whom are far removed from the continent.

“A lot of Africans in diaspora might not have the resources to travel back to Africa…some have the idea that Africa is a jungle where lions are chasing everybody. That’s not the truth. But how do you change that narrative without them visiting?”

Through CYSTADS, he envisions virtual tours tracing slave routes from Badagry to the Americas, immersive experiences of Lagos, and even guided journeys that could lead someone to discover their Nigerian ancestry and, eventually, citizenship.

Family trees are already being digitized, with gamified rewards encouraging users to document personal and collective histories.

“We know history is boring. But we want people to learn about themselves. We’ve created a system that rewards you for trying to understand your ancestry. For everything you add, you are rewarded for that effort.”

Some say the greatest resource Africa has is our land. Some say it’s mineral resources. But you, Richard Afolabi say, is memory. Why?

Afolabi’s gaze sharpens. “A friend of mine said, ‘The future belongs to people who see data when others see gibberish.’

Data is what is in memory. Data is the gold mine that makes Facebook what it is today, that makes TikTok what it is today. Every industry in the next 100 years will run fully on data.”

He describes the deliberate erasure of African history as a strategic disempowerment.

“Whoever controls your story controls your reality. Why was there a deliberate effort to make sure Africans didn’t know their history? Why is Jesus Christ better than Shango in your story?”

He continues, unflinching: “If they want to take things from you, they have to make you question your own reality. If you don’t know who you are, how can you negotiate for better?”

For Afolabi, “Memory is far more important than resources. Once we know who we are, we can ask, what do we do with things we have?”

Related Story: How Tigist Kebede is Transforming Ethiopia’s Film Industry with habeshaview

Bekkah AI aimed to automate African lives. So what does automation mean in an African context?

Here, Afolabi’s vision becomes tactile. “Over 50% of farmers in Africa are women. How do we automate the life of a woman in a remote location who doesn’t have access to good internet?”

Using satellite imagery, drones, and collected data, Bekkah AI predicts optimal crops for a given hectare and coordinates communal machinery to maximize yield.

“This woman is no longer farming to sell. She already has people who will take her product. It changes her mindset from survival to having the resources to build something beyond farming corn.”

Automation, in Afolabi’s view, is liberation. “If we can help Africans make their life easier, they won’t think all hope is lost. They can focus on productive things that build a better Africa.”

From automated market deliveries to autonomous vehicles, Bekkah AI envisions a continent where technology is accessible and practical.

“The implementation is more strenuous than what I just explained,” he admits, but the principle is clear: data-driven automation can empower, freeing Africans to thrive rather than merely survive.”

“Once we start knowing who we are, we can start using the information we get from who we are to change ourselves in ways that help us compete globally.”

How do you balance data protection, privacy, and preservation?

Richard Afolabi leans back in his chair, a faint smile playing on his lips as he considers the weight of the question.

“For us,” he begins, “whatever data you don’t want public is never going to get public.”

It’s not just a policy; it’s a principle etched into every line of code and every decision at CYSTADS, the hybrid platform part-tech, part-museum, part-spiritual archive.

He explains the measures they take with a calm intensity. “We have a team of… I don’t like calling them hackers. We are testing our application consistently. I think we just did one last week.”

The goal, he says, is to stay ahead of threats before they find a weakness.

“Sometimes cyber threats don’t come from someone being malicious. It just happens, someone gains access they weren’t supposed to have, and what they hear or see can later become catastrophic for the business.”

He talks about consent with a mix of pragmatism and vision.

“There’s also the part where your data can be used to train models. But we ask for permission from users. We want Africans to have a more customized experience on the application. There’s no way to do that without data.”

Privacy and personalization coexist carefully. Users choose what stays private, what can be used, and every step adheres to regulatory standards.

“We abide by the rules…we’re working on getting the licenses because very soon, we’ll exceed the numbers. We’re already working with local bodies for licenses.”

Read Also: How Alfi Oloo Broke into Product Design Without a Degree

What is the business model of CYSTADS, a part-tech, a part-museum, and an archive??

Funding for CYSTADS is surprisingly straightforward. “Bekkah is the big brother. Bekkah is sponsoring almost everything on CYSTADS,” Richard says.

And Bekkah, a consulting firm, provides the revenue that keeps the archive alive. “I always tell people, if you’re building for money, you might be frustrated before anything happens that will change your life.”

Richard’s philosophy is clear: money follows value and ingenuity.

“If you have all the money you need to build it, you most likely won’t get creative. But if you don’t have enough money, which is enough money, you become creative with the solutions you really need.

”This constraint has shaped CYSTADS, forcing innovation and adaptability. “I would lie if I said that had we had all the money from the start, we’d be here building what we are building now. We wouldn’t.”

And while external funding might eventually enter the picture, Richard insists it isn’t the right time.

“We’re not ready for that yet…people don’t know that there’s something like too much money. Money can choke you, make you lose the creativity you started with, and prevent you from creating a sustainable system.”

When CYSTADS succeeds, how do you want Africans to introduce themselves?

Richard’s voice rises with fervor as he paints a picture of an African renaissance.

“Africans should start introducing themselves as the cradle of human civilization. They should tell people, ‘We started whatever you are experiencing as civilization.’”

Pride, not shame, is the message. Africans are creative, resilient, and triumphant.

He rejects narratives of victimhood.

“We are not a nonprofit project, we are not the pictures you see online, we are not backward. Africans are building unicorns. Africans excel exceptionally, even in weak systems.”

Cultural confidence, he believes, will empower the continent. Tattoos, names, rituals, and art should reflect African identity, not borrowed symbols from elsewhere.

“Africans will be proud of who they are, and we’ll restore continental identity.”

If you could archive one truth for every African child 100 years from now, what would it say?

Richard pauses for a moment, the weight of history and future pressing upon him.

“You’re not a descendant of failures. You are a descendant of champions, conquerors, and leaders of empires. You’ve been positioned on a continent with enough resources to change global power dynamics. The code in your DNA is part of the power to unlock the greatness the world needs to survive and thrive.”

It’s a message of empowerment, of ancestral inheritance. He speaks with a certainty born from conviction: African children should grow knowing that they are part of a lineage that shapes the world, not merely survives in it.

What lesson have you learned so far in your journey as an entrepreneur?

“The fact that you don’t need to have everything to start. I’m a weird perfectionist. I like all the ingredients before I start cooking. But in entrepreneurship, you just have to start.”

CYSTADS itself is proof of this principle.

“The ideas aren’t given at once. You get clarity line upon line, precept upon precept, and your understanding grows as you move.”

Resilience is another lesson.

“No matter how persistent the problem is, it will always solve itself. Don’t die before the problem is solved. Even debt, even extreme stress, it will sort itself out if you keep a clear head.”

He recounts moments of personal struggle, of depression under financial strain, but emphasizes that composure and strategic thinking are indispensable.

“As an entrepreneur, one of your best friends is debt. One of your best powers is debt management.”

Read Also: Why Dr. Gozie Ezeh Started ‘SweetMom’ to Support First-time Mothers in Nigeria

Where do you see Bekkah AI and CYSTADS in the next 5 years?

Richard Afolabi sits back, “All my projects, I see them in a view of 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100… when I’m not here,” he says, his voice carrying both wonder and conviction.

“And I don’t know, maybe by 2030 or 2050, we will have immortality, hopefully. Because I heard they’re working on things like that in China and Russia.”

In his vision for the next five years, CYSTADS is no longer just an idea, it’s a bridge. A platform connecting West Africans and the diaspora to their roots, history, and even the possibility of relocating.

“Regardless, America won’t tell us yet,” he laughs, hinting at a cheeky skepticism. Yet the ambition is unmistakable: within five years, he expects one to three million people in West Africa and the diaspora to engage with CYSTADS.

Currently, the platform already has users in Kenya and Uganda, but Richard sees a far bigger horizon.

“With the resources we’ll be generating from the platform, we’ll be able to impact lives,” he says.

He frames Bekkah AI as the parent, the “mother company” that incubates ideas like CYSTADS and provides them with funding and structure.

His goal is not just regional relevance; he dreams of Bekkah becoming a global player in the African tech ecosystem, competing in automation, robotics, and beyond.

“Yeah, that’s where I see us in the next five years,” he affirms, a mix of resolve and excitement in his tone.

Related Story: Nonhlanhla Shembe on Why “Visibility is Currency” for Small Businesses

What advice would you give to others who want to venture into entrepreneurship?

Entrepreneurship, Richard insists, is not a calling everyone is wired for. Even he questions whether he was naturally suited for it.

“The only thing that might be the difference between me and every other entrepreneur out there,” he reflects, “might be the fact that I was born into a family that was big on being entrepreneurs.”

His parents ran businesses long before he could even spell the word, creating a home where enterprise was as natural as breathing.

Yet Richard’s advice for young people starting out is rooted less in pedigree and more in discipline and service.

“Try to serve others first,” he urges. “Because in serving others first, you would learn the skill set required to build your own thing. That’s one thing that helped me.”

He is frank about the struggles.

“Entrepreneurship will test you. It might make you even want to kill yourself. Because on some days, it’s not even just about the resources. It’s about certain things you are doing that are not working back to back.”

He even jokes about feeling pursued by “village people.”

Richard emphasizes preparation. “Before you jump into it, learn from people. You can get a mentor, get someone that has your interest at heart, and that can guide you, that can help you become a better human.”

For Richard Afolabi, entrepreneurship is not just a career path; it’s a lifelong navigation of service, impact, and vision, built on the foundation of lessons learned and opportunities seized.

Contact or follow Richard Afolabi:

Leave a comment and follow us on social media for more tips:

- Facebook: Today Africa

- Instagram: Today Africa

- Twitter: Today Africa

- LinkedIn: Today Africa

- YouTube: Today Africa Studio